The name of Katie MacDonald and Kyle Schumann’s firm After Architecture suggests architecture’s demise, which is probably an unwelcome prospect for many architects. The name also suggests that architects might collectively be able to choose their fate, for what comes after. For Le Corbusier, the choice was architecture or revolution. For Mies van der Rohe, the choice was between less or more. For Venturi, it was also between less or more (more or less). What comes after architecture, then? A both/and plurality of architecture and whatever it isn’t. Obviously. (Venturi would approve.)

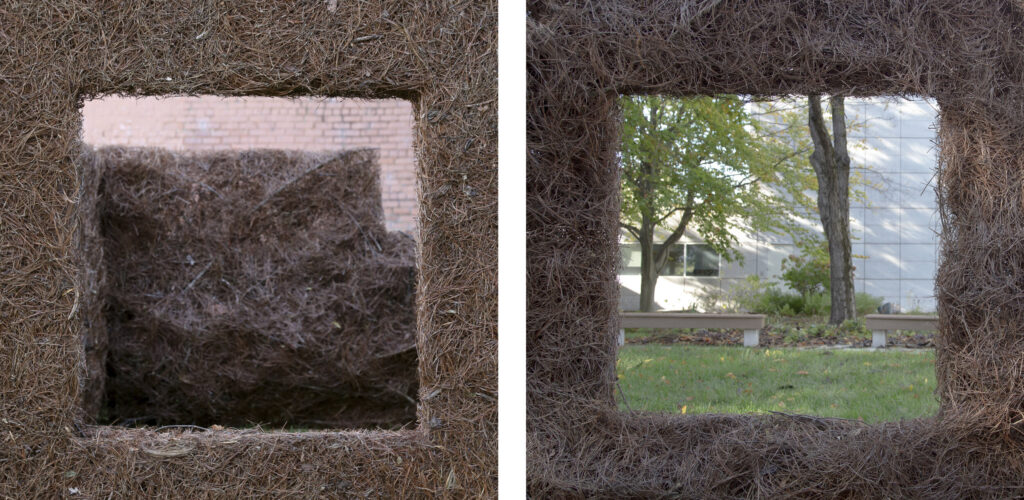

MacDonald and Schumann’s recent project “Homegrown,” installed at the Knoxville Museum of Art in 2020, points to a future for architecture that is about possibilities, for a profession that has more to offer when it does more with less, and creates less by using more of what’s around. For its six-week tenure, “Homegrown” was a small room constructed of walls made of invasive plants and yard waste. That’s it. No program and no real future. But, its construction leaves us with a series of questions about the nature of architectural production: Must we destroy in order to make? Is zero-waste production possible? If so, is it scalable?

Prior to installing “Homegrown,” the Charlottesville-based team had been experimenting with “pillow forming,” which they define as the digital fabrication of irregular surfaces through actuated modular pneumatics and, unofficially, it’s a way to create structure over which organic materials (like bamboo and kudzu, in the case of “Homegrown”) can be shaped.

“For this project, we used a bio-based material binder,” says Schumann. “When mixed with the binder and formed, the material stays together in the designed geometry, producing lightweight walls that were easily transported and assembled on site.”

Each surface is unique, as would be expected with pressurized and glued organic discards, and each surface is both structural and ephemeral—as thick as a wall when compacted and as thin as a twig when observed up close. The outer surfaces are rectilinear and faced in pine needles, while the interior surfaces of the room undulate according to the pillow forming molds they created.

The project began as an outgrowth of an architecture studio MacDonald and Schumann were teaching at the University of Tennessee as part of a fellowship in 2019. Students were to investigate invasive species and ways to transform them, which dovetailed with the duo’s investigation into how pressured air could create geometries in space that had structural integrity and utilize materials that were never intended to be used structurally. That’s how pillow-forming began, which they describe as a giant air mattress controlled by a machine. Their project stayed up for a month and a half, and they completed it with a total budget of $8,000, which included design, fabrication, transportation, and installation (not to mention fabrication of the pillow-forming machine, itself).

But, at the end of the day, what purpose does an unprogrammed outdoor room have, no matter how ingeniously it’s been created? For After Architecture’s principles, “Homegrown” isn’t about finding new ways to contain our ambitions for living space. It’s about containing our bad habit of ignoring materials that are immediately available. It’s productive waste, not wasteful production.

“In terms of productive versus unproductive space,” says Schumann, this project addresses material streams. Relative to the spaces we’re creating, we see this as a prototype and a proof of concept for the public to show we can make walls in this way.”

Beyond found materials, MacDonald and Schumann are also working on a series of furniture composed of grown materials, and curating an exhibition opening at the University of Virginia on March 14 called “Biomaterial Building Exposition,” which will feature the work of five design teams who will create pavilions in a vein similar to “Homegrown.” They’re in a similar vein because “Homegrown” is less of a reproducible product and more of a provocation, says MacDonald, which extends beyond architecture through landscape architecture, environmental sciences, and building sciences. In the end, the goal of the project is meant to be reproducible — to develop it into a viable system and start thinking about things like thermal capacity, the materials stream and the broader pipelines of production, and what it might mean to think about using this approach at larger scales.

“There’s an ecological scale here and a regional scale because waste has to go somewhere, but if it doesn’t have to go that far, then that’s a positive for the environment,” she says.

About the author

William Richards is a writer and editorial consultant based in Washington, D.C. From 2007 to 2011, he was the Editor-in-Chief of Inform Magazine.