Members of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) have been architectural patrons in Washington, D.C. since 1905 when Edward Pearce Casey’s design for their Memorial Continental Hall was completed one block north of the National Mall. Locals know its central meeting space, genealogy library, and museum from DAR’s annual open house, and for almost 120 years, Memorial Continental Hall has been the center of the organization’s activities, debates, and votes.

Locals also know the adjacent Constitution Hall, designed by John Russell Pope in 1924 and completed in 1930, as the scene of hundreds of concerts, comedy shows, military band performances, and upwards of 40 graduations each year for area schools. Its National Register nomination notes its original purpose for DAR’s annual congress was surpassed soon after it opened by its new status as the “unofficial cultural center for the Nation’s Capital.” Even today, if you live within 50 miles of it, you’ve probably been there at least once to enjoy something from one its 3,702 seats (making it the largest concert hall in the District).

Quinn Evans worked with DAR for more than 10 years to restore and refresh elements of Memorial Continental Hall and Administration Building and, starting with a 2014 feasibility study, Constitution Hall. The team restored the U-shaped lobby and upgraded its mechanical systems, restored the stage area, and restored and upgraded the auditorium, itself, including structural reinforcements, safety measures for riggers above, and basement and backstage dressing rooms for visiting acts that might host a church choral group from Cincinnati one day and Bob Dylan the next and then Tina Fey and Amy Pohler the week after.

Pope’s edifice is striking for its perfect Neoclassical temple front that rises above 18th Street. The drama of approaching from the south at an oblique angle is heightened by the road’s gentle elevation change and the facade offers a strong counterpoint to the stripped down Classicism of the Department of the Interior’s flank across the street. The drama that most will remember, however, is inside the main hall as part of a $18 million restoration by Quinn Evans, earning it a 2022 Award of Honor for Historic Preservation by AIA Virginia.

“The goal was to be as accurate as we could be in the restoration, but also provide the kind of flexibility that contemporary performances need,” says Katie Irwin, AIA, a senior associate at Quinn Evans and project manager for the Constitution Hall renovation. “The client’s values really aligned with Quinn Evans’ values in the work we do and in terms of wanting to be great stewards of historic properties.”

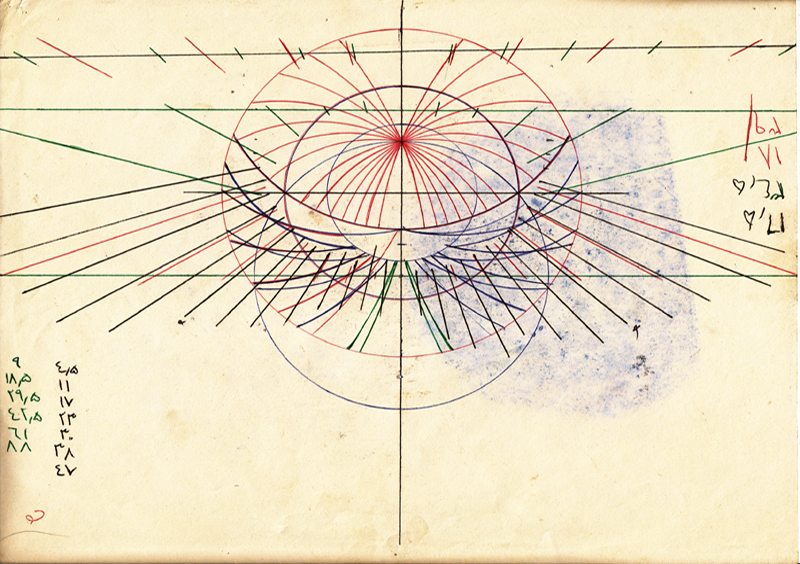

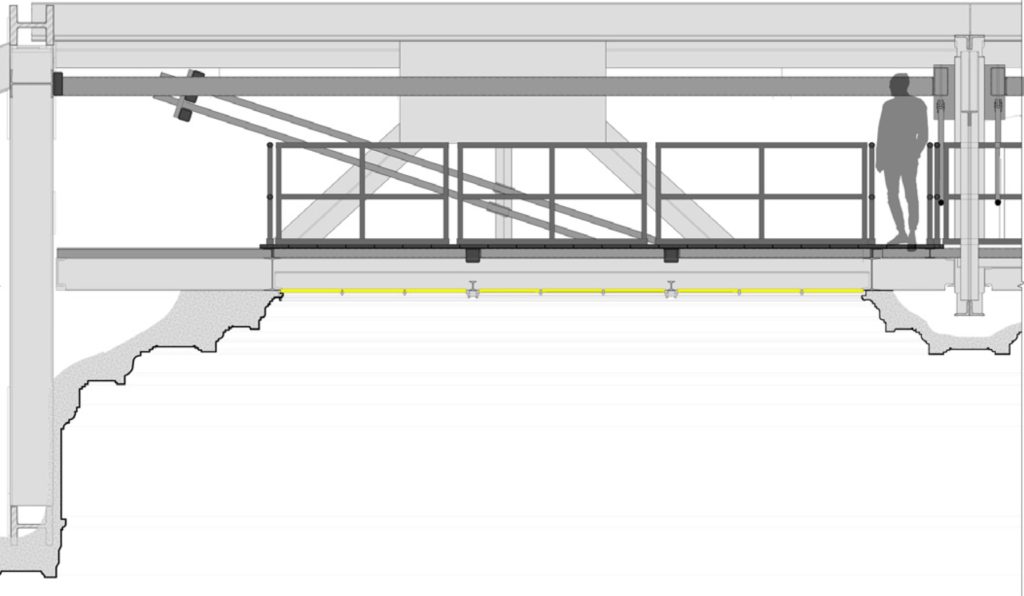

Perhaps the most noticeable difference for concertgoers who’ve been attending shows there for the last 20 years will be the resurfaced coved ceiling, which gently meets the flanking walls of the auditorium. It was rebuilt and resurfaced to gently bounce uplighting while also focusing the eye along its lines towards the stage. It also frames the laylight in the center of the ceiling that’s been framed by a grid. Once powered by the sun, the existing laylight has been retrofitted with 972 LED lights manufactured by Folio in Brescia, Italy, which use a small amount of electricity while providing the soft, diffused luminescence the hall requires. As part of the hall’s upgrade, Quinn Evans was able to stash a fully accessible platform for riggers to hoist lights and speakers above the laylight. The added bonus of using LEDs is that lighting technicians can adjust it to suit different moods, as the performer on stage or the event requires.

“It’s a complex system that has a daylight mode and a starlight mode, so it can twinkle, too,” says Anne Kopf, AIA, an Associate at Quinn Evans and project architect who led construction administration on-site and managed the design and engineering teams on the project.

To that end, there are a few other theaters in town of the same vintage that are on the National Register of Historic Places. The Warner Theater opened in 1924 (as the Earle Theater) has a capacity that’s about half of Constitution Hall’s, and remains a popular venue for artists as diverse as P.J. Harvey and Animal Collective, the horror film director/composer John Carpenter, or–this month–a mariachi band from Tecalitlán, Mexico. There’s also the Avalon in Chevy Chase, which opened in 1922 with an original capacity of 1,200 (today, as a cinema, it’s closer to 450), and continues its centenary celebration this year with the latest Wes Anderson film and a documentary about Vermeer.

DAR’s Constitution Hall is a different caliber, though, whose exterior makes most (if not all) of the lists of notable architecture in the city, but whose auditorium is on par with the Kennedy Center or Carnegie Hall. “You don’t have a space like this anywhere else in DC,” says Kopf, “and it’s a major draw to attend shows, but the space itself—the restoration—is part of the draw.”

William Richards is a writer and the Editorial Director of Team Three, an editorial and creative consultancy based in Washington, DC.

Project credits:

Architecture Firm: Quinn Evans

Owner: Daughters of the American Revolution (Stephen Nordholt, Representative)

General Contractor: The Christman Company

MEP Engineering: Greenman Pedersen Inc. and Loring Consulting Engineers

Historic Paint Finishes Specialist: Artifex Ltd.

Structural Engineer: 1200 Architectural Engineers

Theatrical Lighting and Theater Planning: Schuler Shook

Lighting Design (Phase 1 – Lobby): Gary Steffy Lighting Design

Acoustical Consulting: Jaffee Holden

Life Safety Engineering: GHD

Stage Mural Recreation: Holly Highfill

Photographer: Ron Blunt Photography