For over two decades, the Center for Design Research (CDR) at Virginia Tech’s School of Architecture has been a beacon of innovation, creativity, and excellence in the fields of architecture, design, and technology. Directed by Robert Dunay, FAIA, Joe Wheeler, AIA, and Nathan King, with a vision to integrate cutting-edge research with practical application, the CDR has consistently pushed the boundaries of what is possible, earning recognition and acclaim on both national and international stages.

It’s also been a beacon for the profession in the Commonwealth (and beyond) for converting curiosity into impact, a key generator of ideas for firms and a vital skill for students to learn, no matter which pathway they take to practice.

“‘Experiential learning’ is about expanding what’s possible by refining and reformulating the studio, creating a context for both students and faculty to thrive,” says Dunay. “There’s a competitive side and there is a side to it that’s about troubleshooting under unpredictable circumstances, which is a team dynamic you’ll find in architectural practice. We teach everyone to think in alternatives.”

Let’s take a closer look at the impressive range of achievements that have marked the journey of the Center for Design Research.

Pioneering Solar Decathlon Success (2002-2018)

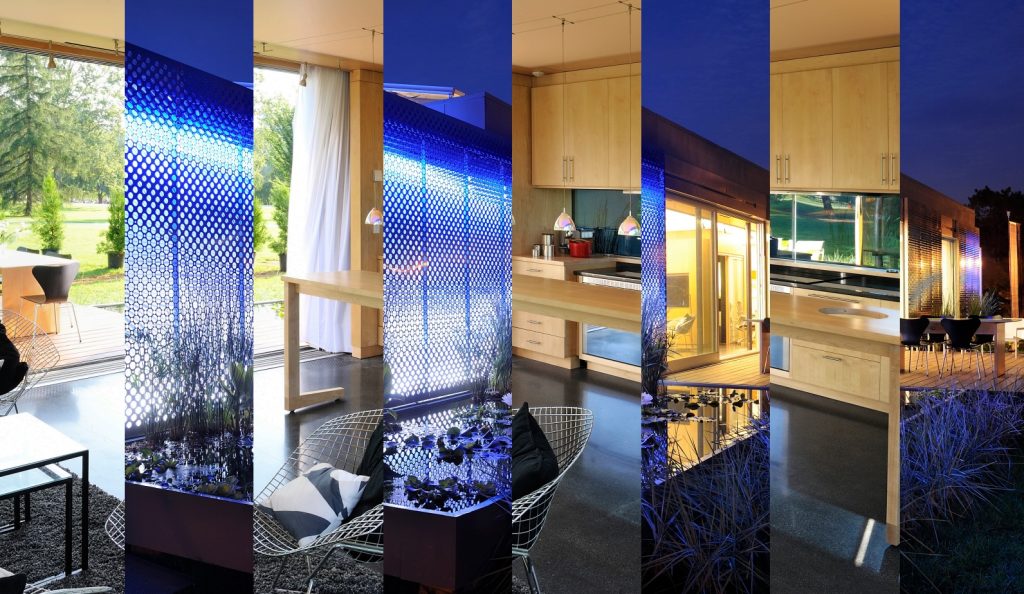

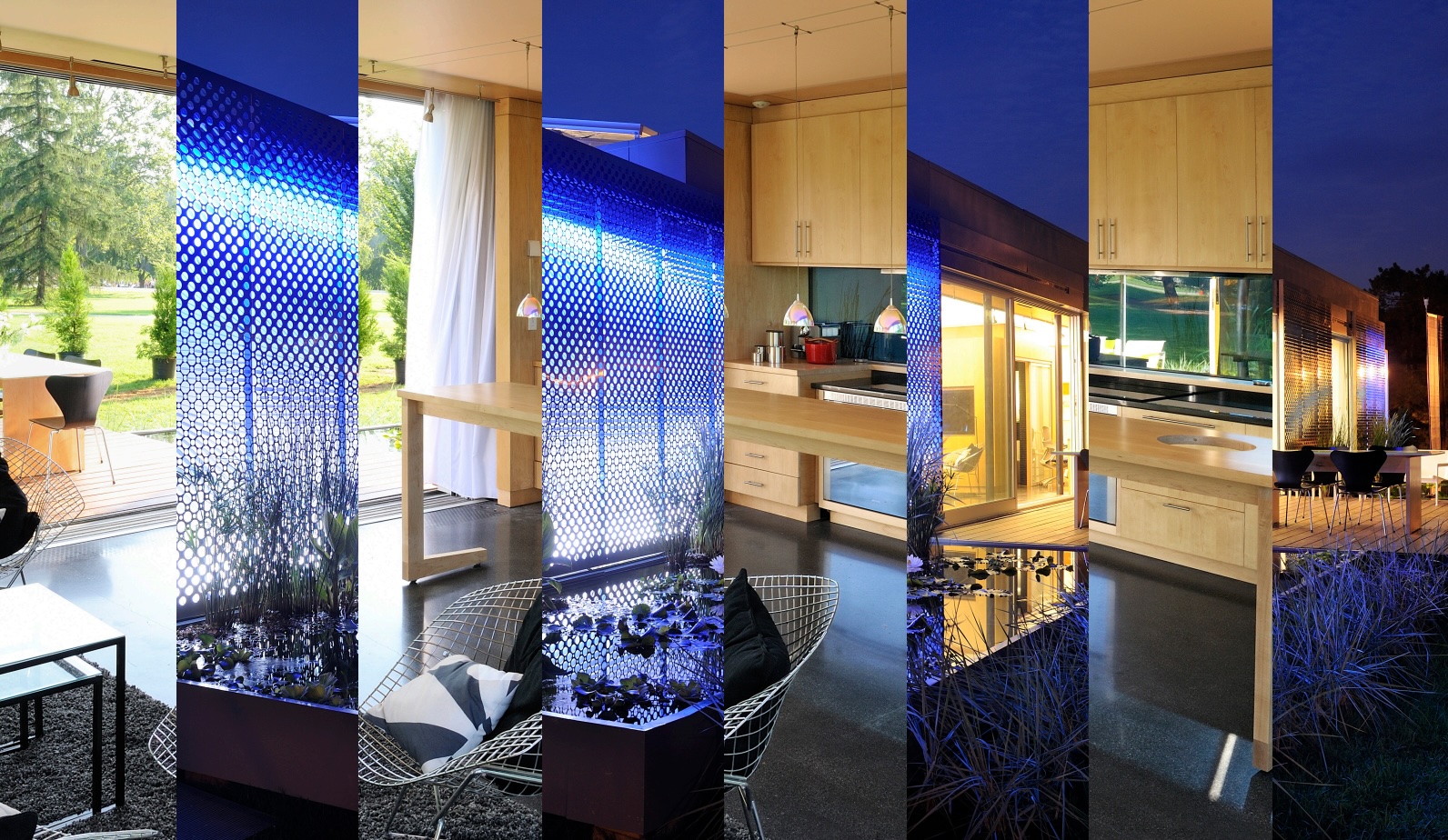

CDR’s journey began with the U.S. Department of Energy Solar Decathlon Competition. In 2002, the CDR’s entry, “The Art of Integration,” garnered the BP Award for Most Innovative House. This success set the stage for a string of victories, including a first-place win in the Architecture category at the 2005 Solar Decathlon with “No Compromise,” and CDR continued its winning streak, culminating in the first-place award at the International Solar Decathlon Competition in Madrid, Spain, in 2010, with the groundbreaking design of LumenHAUS and first place in the 2018 Middle East International Competition in Dubai, UAE.

Global Exhibitions and Collaborations (2003-2019)

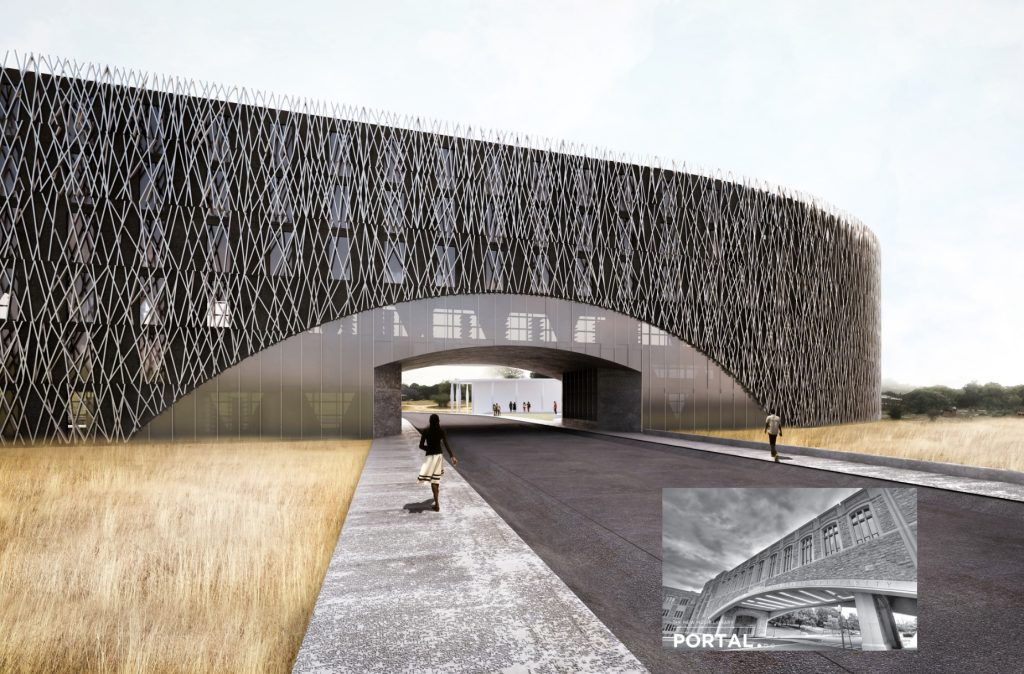

Beyond competitions, CDR has showcased its work on prestigious platforms worldwide. Invitations to exhibit at renowned events such as the International Contemporary Furniture Fair in New York City, the Cologne Furniture Fair in Germany, and the Milan Furniture Fair in Italy underscore the international recognition of the Center’s contributions to design and technology. Notable exhibitions include “The Urban Garden: Innovative Building Skins, Industrialized Processes” in 2012, “F.A.B.R.I.C.A.T.I.O.N.: Technological Material Transformations” in 2015, and “Technology and Tradition: Explorations at the Intersection of High-Tech and High-Craft” in 2017.

Impactful Community Initiatives (2007-2015)

CDR’s commitment to social impact is evident in its involvement with projects like the Extreme Makeover/Home Addition in Blacksburg, Virginia, where the team designed a house and led hundreds of volunteers during construction in just six days. The Center’s reach extended globally with initiatives like the Portable Laboratory on Uncommon Ground (PLUG) in Tanzania, Africa, facilitating research on communicable diseases. The Mzuzu University Library in Malawi, designed with a team of graduate and undergraduate students, is now under construction. Working with MASS Design Group, CDR faculty and students helped with the development of the Gheskio Cholera Treatment Center in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, and the African Design Centre in Kigali, Rwanda. Closer to home, the Eco-Park Learning Center Research Project in Prince William County, Virginia, showcased the CDR’s dedication to sustainable architecture and community engagement.

Recognition and Awards (2011-2018)

The Center’s contributions have not gone unnoticed, with prestigious awards and honors validating its innovative approach to design. The AIA National Honor Award for Architecture recognized LumenHAUS as one of the world’s nine best works of architecture in 2012. Further recognition came after the first-place win at the International Middle East Solar Decathlon when FutureHAUS was invited back to Dubai in 2020 to the World Exposition as the only representative from the U.S.

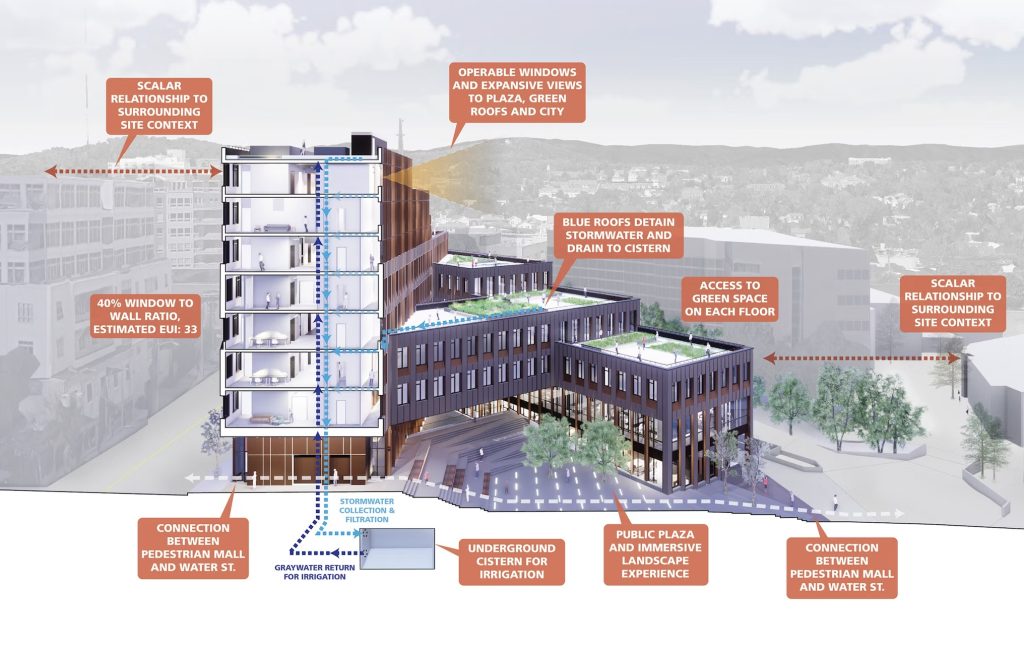

Forward into the Future (2019-2023)

As the Center for Design Research enters its third decade, it continues to push the boundaries of design innovation. Exhibitions in Times Square, New York City, and participation in world expos in Dubai underscore the Center’s ongoing commitment to showcasing its groundbreaking work on a global stage. A clinic designed by Virginia Tech students was recently constructed in Entebbe, Uganda, and has served thousands of patients in the community as the hub for distributive healthcare activities to rural villages in the area on Lake Victoria. Presently, the CDR is working with an NGO called Transcend Institute International to design a prototype academic and trade high school to help revive public education throughout Liberia. Collaborative initiatives like the series of workshops titled, “Democratizing Design Technology,” a grant to increase research collaboration with other universities, demonstrate the Center’s dedication to fostering interdisciplinary partnerships and advancing the field of design research.

CDR has carved out a legacy of innovation, excellence, and social impact over the past two decades. From pioneering solar-powered housing solutions to exhibiting at prestigious international events, and from a research outpost built by students in Blacksburg, and deployed in a remote research post in Tanzania to a robotic, 3D-printed NASA space habitat proposed for Mars, the CDR’s achievements reflect its unwavering commitment to pushing the boundaries of design and technology. As it looks to the future, the Center remains steadfast in its mission to drive positive change through collaborative research, visionary design, and sustainable practices, leaving an indelible mark on the world of architecture and design.

Want to learn more?