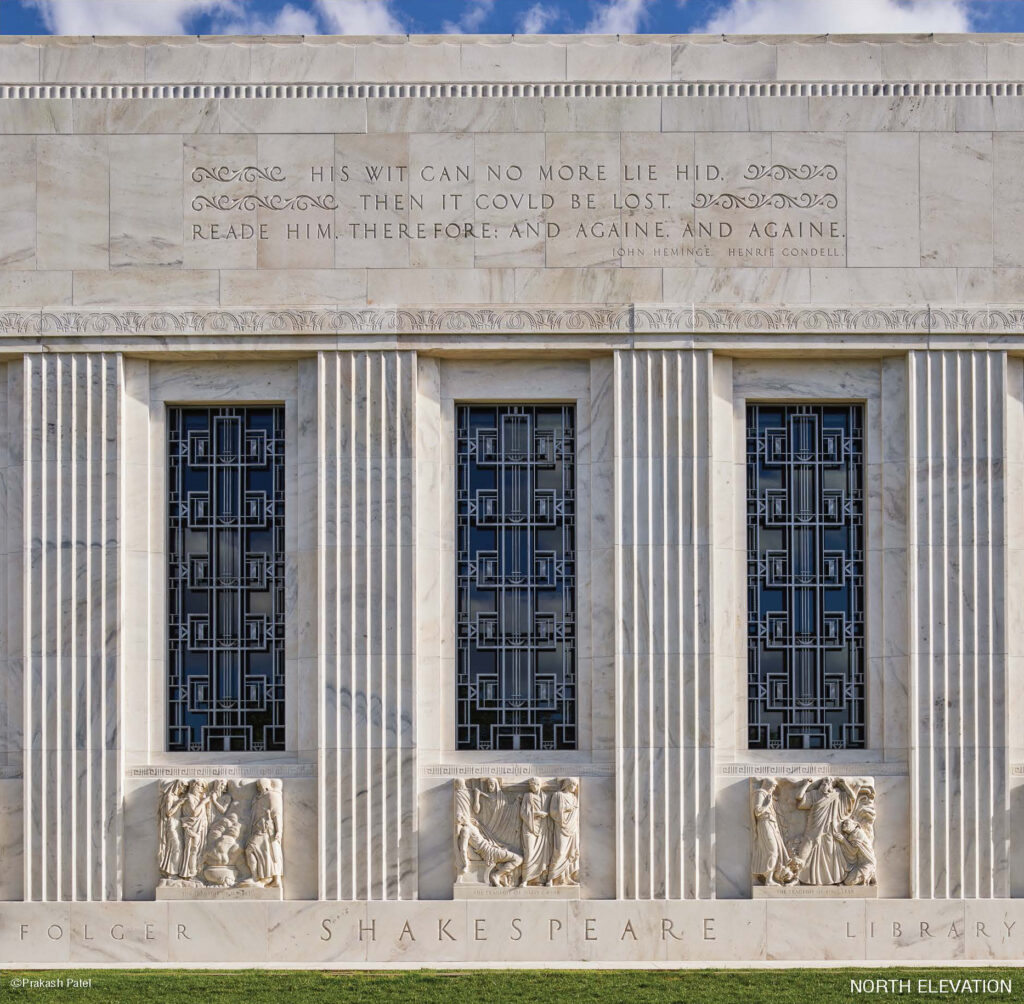

MTFA Architecture’s award-winning conservation work for the Folger Shakespeare Library revealed clues about how similar marble-clad buildings from the WPA-era could be renewed for new generations of visitors.

This one happens to be soft Georgia marble from a half-mile wide vein in Pickins County (which can also be found in Daniel Chester French’s statue of Lincoln on the National Mall, half of the Canon House Building next door, and the East Wing of the National Gallery of Art on the other side of the Capitol). Soft, in this case, means absorbent, and over nearly a century, the facade absorbed rainwater carrying metallic ions from the exposed copper flashing below the parapet, reports Amanda Edwards, the Folger’s lead conservator for MTFA, and a materials testing, analysis, and condition assessments expert. “Once the metal ions are absorbed, they do not get rinsed out and the metal ions begin to corrode within the pore structure of the stone. The resulting stain is further absorbed by the porous stone.”

The conservation and design team developed a new deep-cleaning protocol that centered on the lightest possible touch: a poulticing process of applying a thin paste to lift impurities, microabrasive cleaning to renew the surfaces, and misting to bring the building back to its original grandeur. For this protocol to work, says Edwards, it had to be reimagined at the scale of the building. “Poultices are not new but they are rarely used on whole elevations. They are more generally used for spot cleaning,” she says. “At the Folger, the stain occurred below the parapet for the full perimeter of the building, so we had to figure out how to apply the poultice in an efficient way, at the right thickness, and without letting it dry out too quickly.”

Trial and error, she notes, was also an important part of the process of cleaning the facade. The stain could not be lifted right away, especially since it had seeped deeply into the marble, so Edwards and her team had to power wash the marble, then gently mist it for several hours to create conditions for the poultice to also seep into the marble. “Learning how to apply the right sequence to the whole building was the biggest challenge,” she says. “We tested and perfected the sequence on the rear elevation before we moved to the more prominent elevations.”

The effort paid off and the Folger has returned to its former glory (although, let’s face it—it’s always been a striking building). In 2020, AIA Virginia recognized MTFA’s work on this National Register building with an Award of Honor for Historic Preservation, with jurors citing the cleaning and color-matching process as textbook historic preservation of Cret’s original materials and craftsmanship. Cret’s commission at the top of the Great Depression might have been doomed, but design and construction took a relatively short four years. His clients, Standard Oil’s President, Henry Clay Folger, and his wife, Shakespeare scholar Emily Jordan Folger, worked closely with Cret, whose other contributions to Washington, D.C. included the Pan-American Building for the Organization of American States and the Federal Reserve. But, it’s his contribution in the form of the Folger that forms a big part of his legacy: the most successful and perhaps handsomest marriage of International Style Modernism and Classicism in the nation’s capital.

About the Project Team

Architecture Firm: MTFA Architecture

Owner: Folger Shakespeare Library

Contractor: Dan Lepore & Sons Company

Photographer: Prakash Patel Photography

About the Author

William Richards is a writer and editorial consultant based in Washington, D.C. From 2007 to 2011, he was the Editor-in-Chief of Inform Magazine.