Bow ties are still worn today, but not as popularly as they were two generations ago. For architects, bow ties have always been sartorial and functional — the less fabric dangling over your mayline, the better. Beyond fashion (and architecture), bow ties can signal class, disposition, vocation, and political allegiance. Bill Nye and Tucker Carlson are both passionate devotees, as were Karl Marx and Groucho Marx. Wearers spark uncommonly strong reactions by non-wearers, from endearment to hostility. One New York Times correspondent called the bow tie a “red flag that comes in many colors,” while one Virginian-Pilot correspondent concluded that, “bow tie wearers are not like the rest of us.” Pre-tied and self-tied divide wearers, as do different styles such as the butterfly, the batwing, and the diamond point.

There’s also a mythology about crooked bow ties, in particular. Some say if it’s crooked, you’re doing it right. Others find it appalling. What does an architect say, then, when a client gleefully holds up your plan for their new home and says, “It looks like a crooked bow tie?” You call it the Crooked Bow Tie House and you reap the benefits of organic Google search results between the actor Rami Malek’s scandalous knot at the Oscars and advice on how to straighten out a messy tie job.

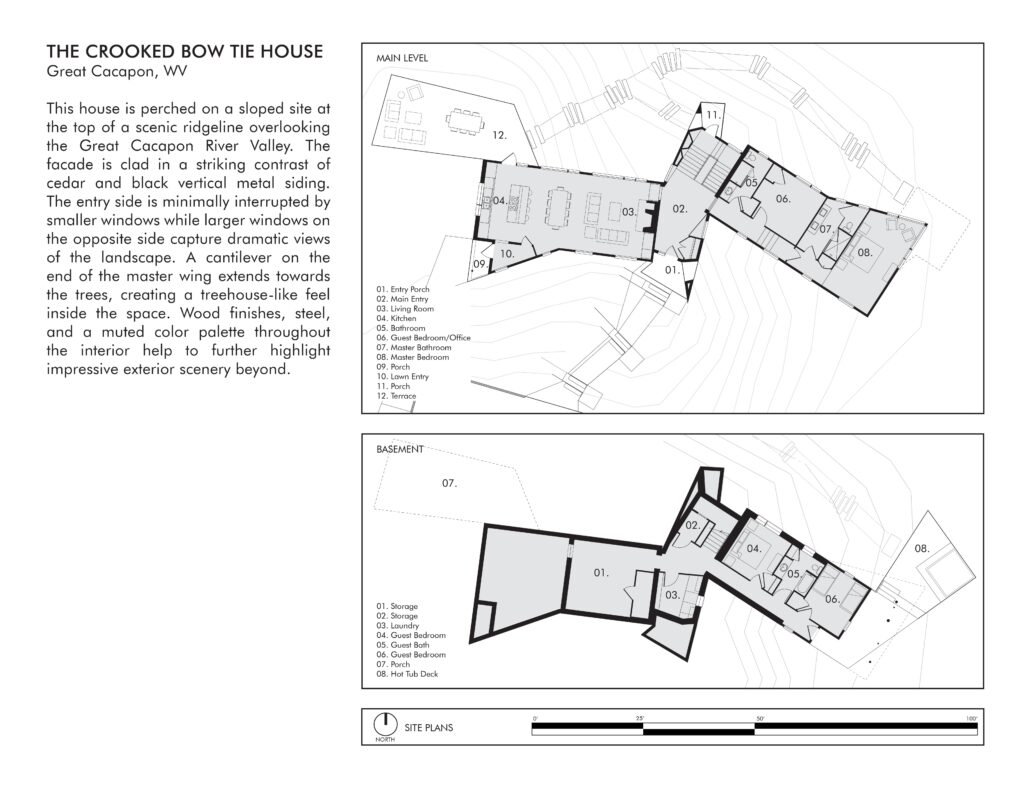

Controversy aside, Reader & Swartz’s mountaintop retreat in West Virginia for a D.C. client looking to escape for the weekend is a 2,878 square-foot house that offers the experience of sleeping in the treetops. The unique plan facilitates viewsheds like a star-shaped Italian bastion fort while also offering a clear programmatic register: enter in the pinched middle and venture out to take in the view. Bedrooms to the right, living spaces to the left. It’s a simple arrangement for a simple goal: get away from the city and relax.

“We asked ourselves ‘how do we create a building in constant dialogue with the landscape and mountains with the least amount of moves possible’,” says Chuck Swartz, FAIA. “You have to know when to shout and know when to be quiet with your design, because there’s always a context to respond to.”

The context in this case is a gated community occupying a crook of land between the Potomac and Cacapon Rivers, nestled in a vale of the Appalachian Mountains. Crooked Bow Tie House, completed in 2019, sits on a hill west of Berkeley Springs, West Virginia, the historic spa and enduring getaway 102 miles northwest of D.C. and just south of the knot, so to speak, of Maryland’s bow tie shape.

“Our client had already done a painful renovation of a D.C. row house, which is a very prescribed housing type, so they were looking for something more open here in the country,” says Beth Reader, FAIA. “So we gave them a place they could retreat to and made the living space very simple.”

Inside, Reader and Swartz frame views with white-painted and cedar-paneled walls and have created generously sized spaces despite the house’s modest overall size. Outside, black-painted steel cladding on the two bow tie wings and cedar on the entry pavilion align with the browns and grays of the landscape defined by a thin layer of topsoil over shale. Its massing rises with the tulip poplars and red maples, and pushes out to meet the surrounding canopy.

“As dramatic as the landscape is, we wanted to give them a dramatic home without pushing the limits of common sense and long term viability,” says Swartz. “This house has to be easy to maintain and be as beautiful tomorrow as it is today.”

About the author

William Richards is a writer and editorial consultant based in Washington, D.C. From 2007 to 2011, he was the Editor-in-Chief of Inform Magazine.