The built environment’s share of global greenhouse emissions is well known, but actionable strategies to reduce them are mired in government and private sector finger-pointing. If you’re an architect at any size firm working on any type of project, you have agency to cut through the blame game to take direct action to decarbonize your work. That doesn’t necessarily mean you have to hit ambitious net zero goals tomorrow (although that would be a great idea at this point), but it does mean you can make a big dent in both embodied and operational carbon in your next project—and across your entire future portfolio.

There are a lot of first steps on that road, but Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) are arguably the easiest. EPDs are reports initiated by manufacturers to outline life cycle information for architects, clients, developers, engineers, and others to compare the environmental performance of materials and products. That information includes (but isn’t limited to) a product’s greenhouse gas emissions and its impact on ozone depletion, its impact on water pollution, and its impact on health generally.

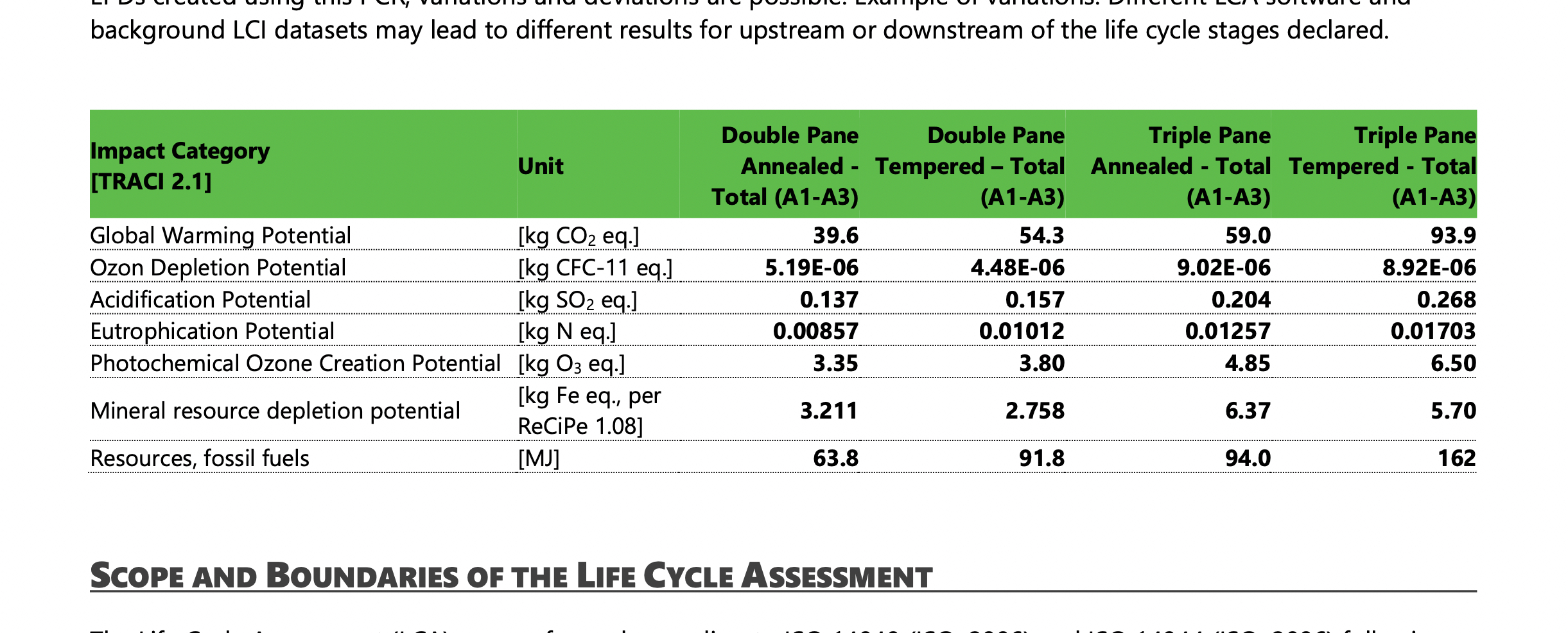

EPDs are utilized in lots of ways—at the product specification stage of a project, as an environmental benchmarking tactic, as a procurement tool to meet government or private sector project requirements, as a marketplace advantage for architecture firms (or product manufacturers), and as the basis of certification credits such as LEED. Individual declarations are for one product by one manufacturer, and they must follow Product Category Rules (PCR) that govern how data is collected as part of a Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA). EPDs are verified by third-party “program operators” such as ASTM, NSF, or UL, and conform to specific International Organization for Standardization (ISO) requirements, which represent an unbiased review process. EPDs are completely voluntary and not required by law or Federal regulation in the United States.

Interested in using one? They aren’t all available in one place and you’ll have to do some digging via EPD databases including the non-profit EPD Registry, the Better Materials Database, or the Embodied Carbon in Construction Calculator (EC3). Not all products and materials are represented by EPDs, and a familiar refrain among architects is having to encourage (and chase down) product manufacturers to complete them. Still, they are worth the effort as key assets to formulate and pursue decarbonization goals at the project level, portfolio level, or even the industry level.

There are also other quick guides and resources available to learn more about EPDs, such as the AIAU course “Embodied Carbon 101: Environmental Product Declarations,” and related AIAU courses covering roofing and an upcoming live one on building envelopes. There is the Alliance for Sustainable Building Products’ upcoming webinar, and there’s the USGBC’s explanation of how EPDs function within their certifications (as well as UL’s own hour-long webinar on the same topic). Last but not least, AIA Virginia’s Committee on the Environment maintains several resources to help you understand EPDs and related tactics to decarbonize your practice (and your portfolio).

William Richards is a writer based in Washington, DC, and co-founder of Team Three, an editorial and creative consultancy. His latest book, Bamboo Contemporary, published by Princeton Architectural Press, is out this month.