Before the advent of air conditioning, Washingtonians endured hot summers as the northernmost southern American city. They coped by moving a little slower for a few months and hopping the trolly to some of the glades dotting the city’s periphery like Glen Echo, Hains Point, Oxen Run, or along Sligo Creek. That periphery is still marked by 40 boundary stones, the nation’s oldest federal monuments, and a network of forts, parks, and recreation centers that serve as neighborhood hubs. Marvin Gaye Recreation Center is the newest public facility in the District, completed in 2018 and situated just 1,000 feet from the easternmost boundary stone.

As new as it is for our over-air conditioned age, it’s also a throwback to a time when all you needed were open windows in just the right places to make even sweltering days manageable. The center, designed by ISTUDIO founder and principal Rick Harlan Schneider, FAIA, utilizes natural ventilation to circulate air by pulling it in low and pushing it out high. It’s not a replacement for air conditioning, per se, but a low-tech compliment to the HVAC system that can be deployed for the shoulder months that usher in and conclude summers in D.C.

“We’re looking to emulate the powerful forces of nature — it’s what our studio is based on,” says Schneider, “And, this type of passive cooling is a technology that’s really good in a pandemic, too, because it uses volume displacement to move air away from bodies.”

Schneider started ISTUDIO in 1999 with what he says is the goal of contributing to communities in artful, equitable, and sustainable ways. He is currently part of the project team for “Green City, Blue City, Old City, New City,” an exhibition on display at the European Cultural Center in Venice adjacent to the 2021 Venice Biennale. The team is a collaboration between ISTUDIO and the Washington Alexandria Architecture Center students to reimagine the District in terms of its waterways and green space. The central idea for the ISTUDIOxWAAC team is to “reframe” resilience by pinning future community development to natural cycles and systems that have local and regional relationships. By way of evidence, the team points to ISTUDIO’s Powell Elementary School, Tubman Elementary School, and an unbuilt Kingman Island Environmental Education Center for the Anacostia River.

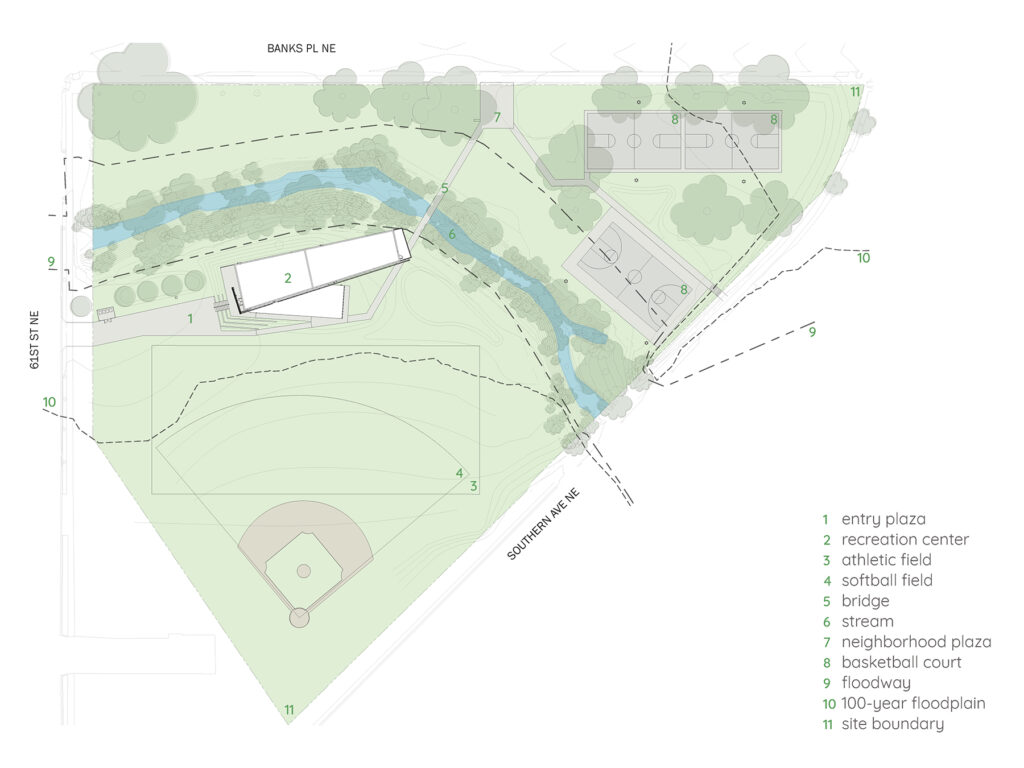

The fourth project that will be featured in Venice is the Marvin Gaye Recreation Center, which sits at the head of Watts Branch, a tributary of the Anacostia that sits in a valley enveloping 438 acres within the eastern precincts of the city and Prince George’s County. It’s a large building at 7,200 square feet — much bigger than the homes in surrounding Capitol Heights — but it feels much lighter than its size would suggest. Part of that has to do with the way the building is sited, anchored to the land and also perched over a stream and a pedestrian bridge below. Part of that also has to do with the way an aluminum screen seems to glide past the steel-clad building behind it.

Scrims and baffles have been deployed to dramatic effect by architects in local projects in recent years, most notably at Frank Gehry’s Eisenhower Memorial off the National Mall. Schneider and project architect Marisa King, AIA, have created a dynamic sense of movement along the façade at Marvin Gaye using their screen. But, the main goal was not aesthetic, but functional and in the service of shading and ventilation. As a LEED-certified Gold building, Marvin Gaye is also one of the District’s nearly 400 LEED-certified properties.

“There’s a sense that biophilia is about checking boxes, but for me, it’s about recognizing patterns in the natural world that we respond to, which may be emulated in our built environment,” he says. “When we design with biophilic principles, the result can help people better connect with the natural world.”

About the author

William Richards is a writer and editorial consultant based in Washington, D.C. From 2007 to 2011, he was the Editor-in-Chief of Inform Magazine.