The parking infrastructure in America is spread out and occupies large pieces of land. As ride sharing mobility increases, parking needs are declining in urban areas around the world. This trend is expected to grow with the advent of autonomous driving vehicles.

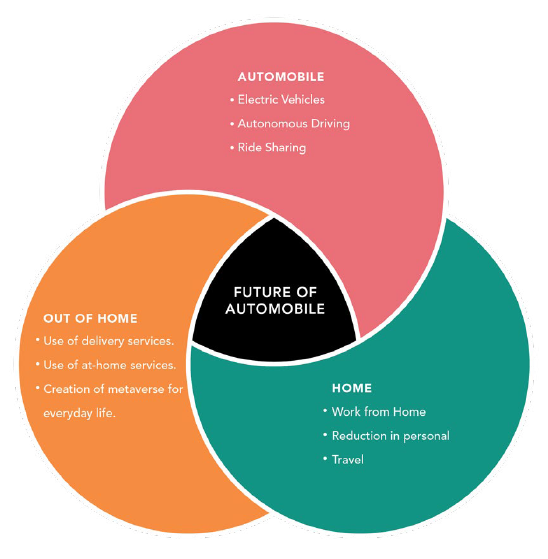

As we recover from the pandemic, mobility has been replaced by communication. This intersection of current global circumstances (due to the pandemic) and transportation industry developments will give rise to a new typology of a transportation system of the future. In anticipation of this paradigm shift, many cities are preparing for this change with policy intervention or by modifying parking requirements for private and public development. Municipalities are recognizing that outdated planning policies make it difficult to build more multi-family homes within urban boundaries, thereby fueling an unprecedented housing shortage that is entirely artificial in origin.

KGD proposes a possible strategy to deal with existing parking structures and how they can be repurposed for the future of mobility to develop a sustainable model of development.

For a time, covid-19 halted life in the public sphere and paused almost all movement in the city. Companies and institutions responded by creating a model for working from home that has implications for how we will work in the future. Some employees are prepared to take pay cuts or even resign from jobs that require a return to in-person presence. One of the reasons for this shift is the expense of commuting, which includes the cost of purchasing and maintaining a car and the time required for travel and parking.

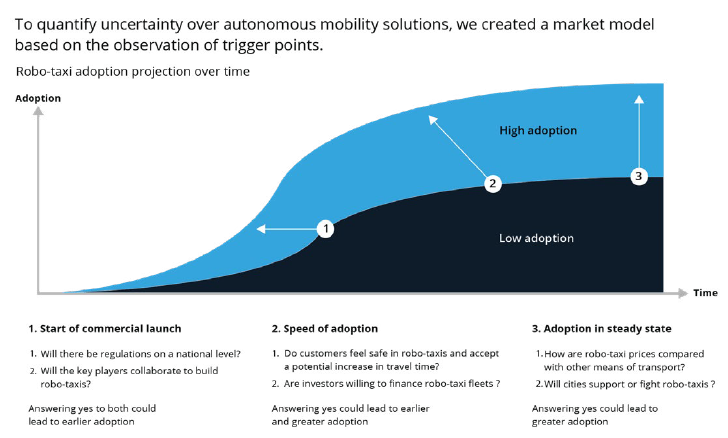

This new model of working is coupled with the advent of on-demand vehicles. During the pandemic, ride-sharing apps expanded their business model to include delivery of goods and services, a move that helped these companies to stay afloat. As pandemic restrictions loosened, people have started to commute to work differently than before by employing on-demand vehicles to transport them to work. Deloitte and McKinsey are predicting an increase in the shared mobility market (Deloitte 2016; McKinsey, 2017). Since 2016, the e-hailing industry has seen an increase of 140% year on year (YOY) versus a 35% YOY increase in shared transportation (car sharing). It is anticipated that electric cars and autonomous vehicles (AVs) will also result in a reduction of travel time. These combined factors will catapult a move toward a more energy-efficient and well managed system of transportation. It is important to have a framework for navigating this transition to shared mobility and put policies in place that allow for positive response to the change rather than allowing change to be led by market reactivity and disruption.

Understanding the Future of Mobility

Traditionally, mobility has been about privately owned 4- and 2-wheel transportation. These vehicles are owned by the user to travel for multiple purposes. The cost of owning, managing, and maintaining these vehicles is borne by a single individual for a vehicle that is used only 5% of its lifetime (Reinventing Parking, 2013).

With the advent of shared mobility, the cost of the vehicle is shared by a greater number of users, which increases the usability of the vehicle and increases the returns on each vehicle. This is the value of shared mobility.

Shared mobility comprises multiple forms of transportation. Regarding shared mobility today, did you know that:

Gearing Up for the Future

As technological developments approach a state of ambient computing, an increasing number of industries will converge under newer, broader, and more dynamic digital ecosystems (McKinsey & Company, 2017). The world of ecosystems will be a highly customer-centric model in which users can enjoy an end-to-end experience for a wide range of products and services through a single access gateway without leaving the ecosystem (McKinsey & Company, 2017).

According to McKinsey, by 2030, AVs, connected cars, electrification, and shared mobility (ACES) will dominate, and we will see developments that may be as profound as those that emerged when the automobile was invented (McKinsey & Company, 2019b). The industry’s focus will move away from such past differentiators as powertrains and concentrate on the car’s embryonic technology stack, a term borrowed from the technology industry that describes the layers of software and hardware that comprise a vehicle’s operating system (McKinsey & Company, 2019b).

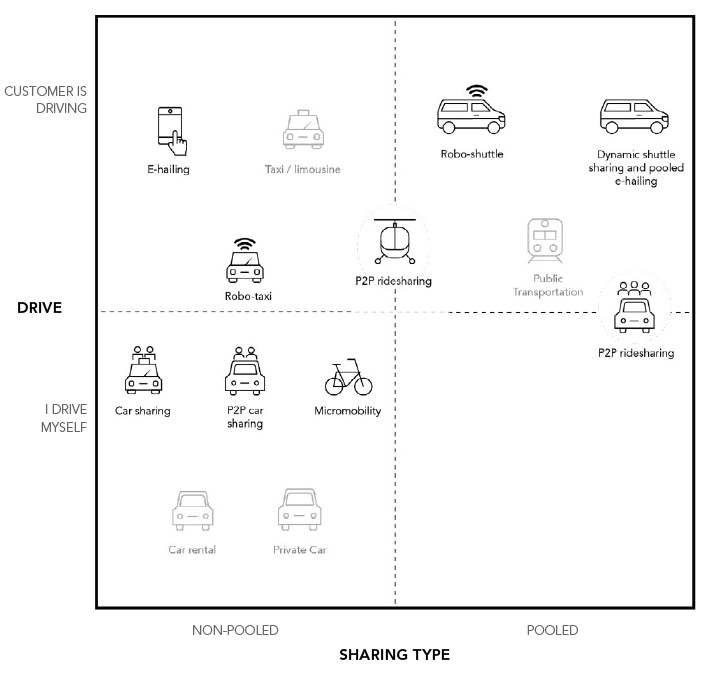

These new technologies give rise to new modes and services that include pooled ridesharing with strangers, peer-to-peer ride sharing, and shared electric scooters and point to a sizable potential market in the mobility space. Autonomous taxis and airborne modes of transportation, in which there has been significant investment in recent months, will also feature in this new model of transportation.

Adaptation of TaaS (transportation as a service)

Transportation-as-a-service (TaaS) is a new model for passengers to access transportation on-demand that provides a level of service equivalent to or higher than current car-ownership models without the need to own a vehicle (Rethink X, 2017).

By 2030, within 10 years of regulatory approval of fully autonomous vehicles, 95% of all U.S. passenger miles will be served by TaaS providers that will own and operate fleets of autonomous electric vehicles providing passengers with higher levels of service, faster rides, and vastly increased safety at a cost up to 10 times cheaper than today’s individually owned (IO) vehicles (Rethink X, 2017).

TaaS could also help companies to work out a transportation strategy for their employees, an effort that will require active participation of companies with their employees to consider such factors as where people reside and their transportation schedule. This strategy is an economical and integrated approach to travel for their employees that can also reduce the corporate carbon footprint.

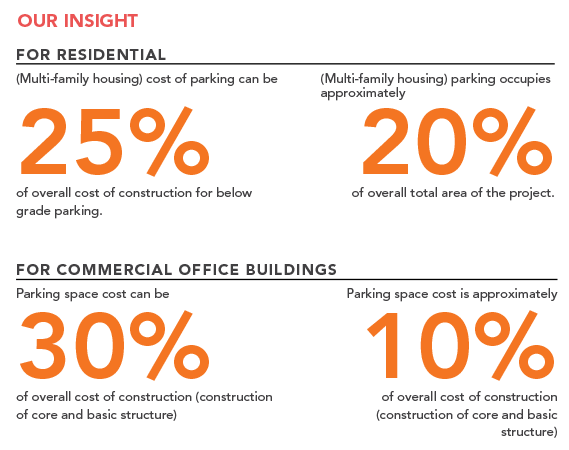

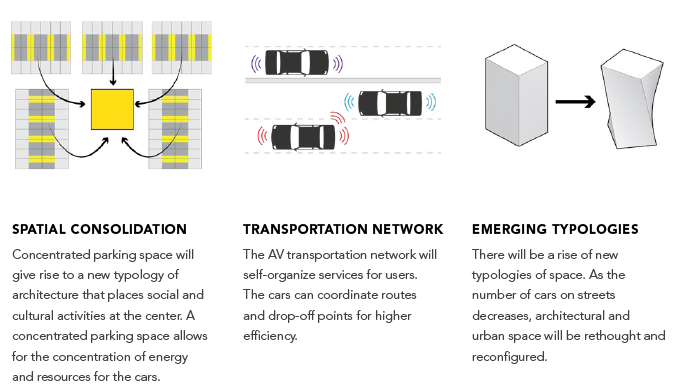

We predict that these numbers will drop and that as they fall, there is the possibility of an emerging typology of architecture and urban design. We have projected what these changes could do to the existing built environment as well as new projects and real estate developments. We do not propose nor do we think it is practical to eliminate vehicles; rather, we propose to establish a new relationship with cars and the changes to transportation on the horizon.

Policy Implications

There are several policy pathways that can assist the development of TaaS in ways that optimize the benefits and aid in the design and planning changes (RethinkX, 2017).

- Revision of building pick-up and drop-off standards that help in developing new typologies of commercial buildings and aid in design explorations.

- Development of planning strategies for the reuse of such unneeded transport infrastructure as parking lots.

- Development of new planning standards for the design of new neighborhoods.

- Increased requirements for green and social spaces in buildings that enable better quality of life.

- Sustainability compensation for institutions that reduce their parking footprint.

Design Implications

Our Proposal

The intent of this research is to understand the future of transportation and to use that knowledge to revisit our relationship with transportation. Post Covid-19 infrastructure should be climate sensitive and build a sustainable life for the community it serves. To this end, our approach includes an understanding of transportation as a regional ecosystem created from new transportation modalities and existing infrastructure. It aims to utilize the existing footprint of previous generations invested in parking structures and use them wisely for the future.

Transportation as a System

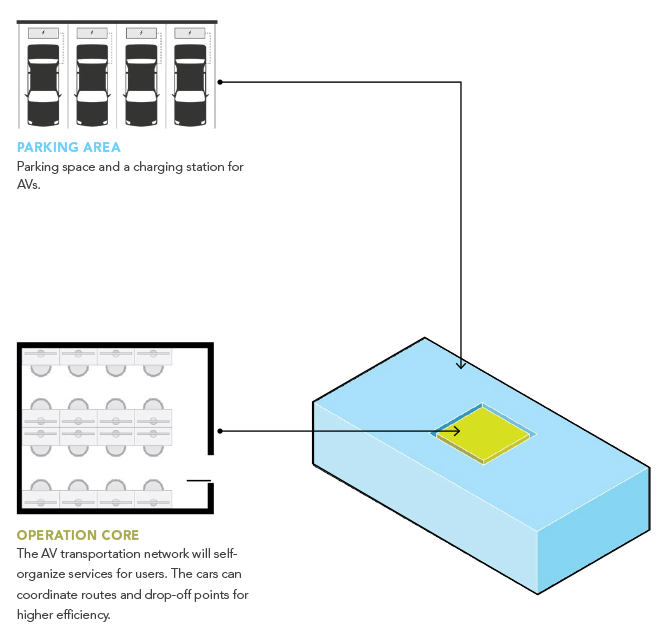

Existing underused parking structures can be used as parking stations for cars that cater to the neighborhood in which they are parked and possibly another local community, depending on capacity and population. This is the basic principle of ride sharing, in which neighborhood residents can book trips serviced by their local cache of automated cars. The car system will efficiently group travelers according to their desired time and destination, thus increasing the productivity of the car and making better use of the resources required to manufacture the vehicle.

Spatial Consolidation

Residential and Commercial Development

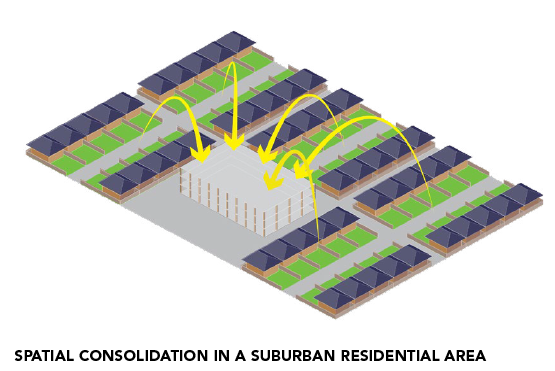

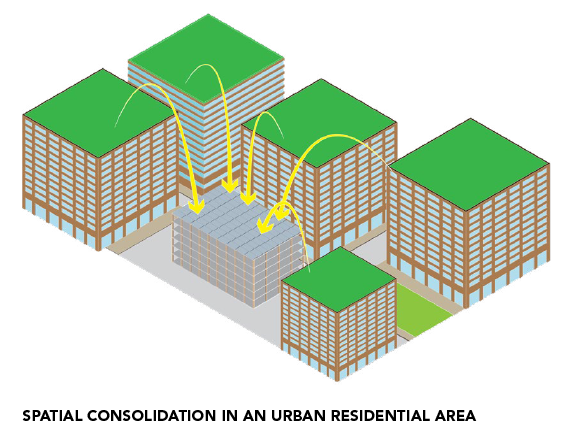

In the future, spatial needs will adapt to the lower number of individual car owners. The spatial needs of parking spaces for regional AVs can be consolidated to a nearby parking structure.

Converting Exiting Parking Structures to AV Centers

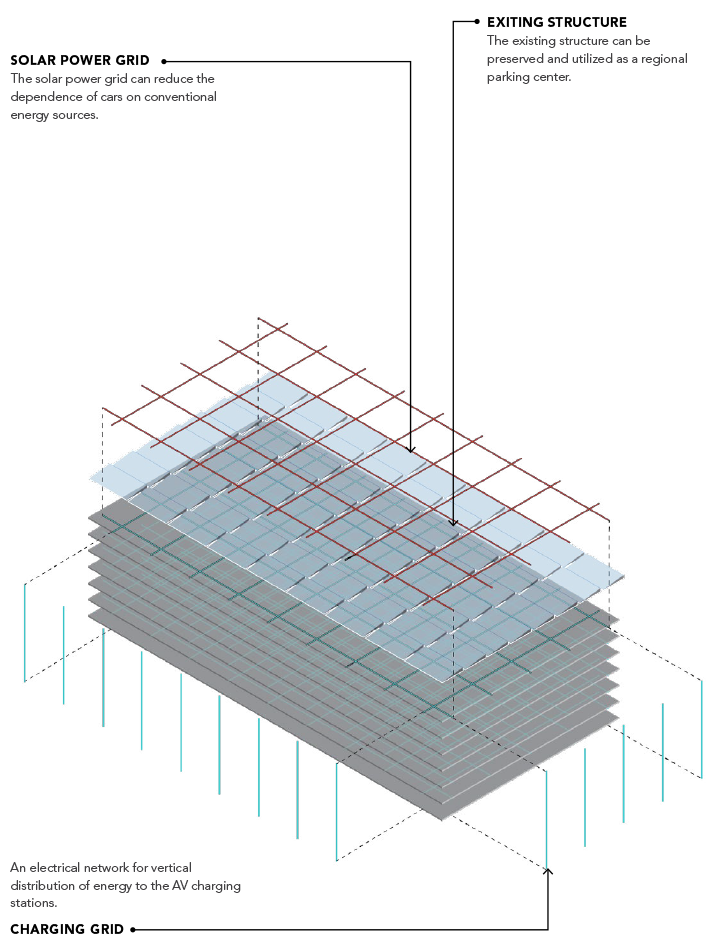

Existing parking structures can be repurposed for use as an AV center that serves as a charging and operation station for the cars. A single AV can cater to several individuals/families thus increasing its productivity.

We created a projection of the emerging typological evolution for new developments. Rather than having a single drop-off and waiting area for the cars, these areas will have multiple pick-up and drop-off areas. As new developments minimize the space allocated to parking, there is expected to be curbside demand for services from AVs.

Conclusion

The world is moving toward a much more sustainable approach to design. Design professionals, policy makers, and clients must continue to adhere to this approach when we consider the future of transportation. The solutions presented here take into account the repurposing of existing infrastructure and the evolution of existing typologies of buildings. Recognizing that every community is unique, these emergent solutions are typology specific and would adapt to the context. They are central to the idea of transportation as a system, increasingly operating in the digital and analog worlds, versus transportation as a mere medium/mode of connection. The system at large is designed with sustainable input to have long-term sustainable output responding to renewable resources of energy, existing land area, building typology, future policymaking, and users.

With this systemic approach to transportation, the reinterpretation of the different modes and user-specific needs lead us to rethink the consumption of cars and the economics of transportation in order to make our cities more sustainable, resilient, and healthy.

This reimagining of how we utilize transportation and how transportation utilizes space has been waiting for the right moment to finally reclaim our cities and spaces from cars and repurpose it for people. Now is the time to rethink “business as usual,” as projects currently in pre-design come on-line in response to a developing transportation ecosystem.

References

- Deloitte (2016) – Gearing for change: Preparing for transformation in the automotive ecosystem. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/focus/future-of-mobility/future-of-mobility-transformation-in-automotive-ecosystem.html

- Deloitte (2018) – The Future of Parking. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/insights/us/articles/4745_FoM-and-parking/4745_FoM-and-parking.pdf

- Rethink X (2017) – Rethinking transportation 2020-2030. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/585c3439be65942f022bbf9b/t/591a2e4be6f2e1c13df930c5/1494888038959/RethinkX+Report_051517.pdf

- Mckinsey & Company (2019) – Development in the mobility technology ecosystem—how can 5G help? https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/automotive-and-assembly/our-insights/development-in-the-mobility-technology-ecosystem-how-can-5g-help

- Mckinsey & Company (2017) – Competing in a world of Sectors. without Borders https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/mckinsey-analytics/our-insights/competing-in-a-world-of-sectors-without-borders

- Reinventing Parking (2013) https://www.reinventingparking.org/2013/02/cars-are-parked-95-of-time-lets-check.html

- Mckinsey & Company (2019) – Change vehicles: How robo-taxis and shuttles will reinvent mobility. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/automotive-and-assembly/our-insights/change-vehicles-how-robo-taxis-and-shuttles-will-reinvent-mobility

- Mckinsey & Company (2021) – Shared mobility: Where it stands and where it’s going. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/automotive-and-assembly/our-insights/shared-mobility-where-it-stands-where-its-headed

This research is published with the permission of the authors.

All rights reserved to the following:

KGD Architecture

Virginia Tech- Washington Alexandria Architecture Consortium

This research was conducted by Virginia Tech student Ameya Lokesh Kaulaskar, with support from Professor Susan Piedmont-Palladino, Director of the WAAC, and Manoj Dalaya, FAIA, and D. Matthew Alexander, AIA of KGD Architecture.