There are some 90 museums in the United States and abroad covering individual aspects of the American Army, from its airborne and artillery divisions to general defense to the personal history of General George Patton, himself. The eighth to open in Virginia alone is the most comprehensive among them in terms of its permanent collection and scope, and its exhibitions program is varied to accommodate a variety of audiences. Yet, the new home for the National Museum of the United States Army, designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) and sitting at the head of 84 acres of land at Fort Belvoir, is entirely singular in its expression.

By car, a winding approach road offers glimpses of the building’s profile through the thicket, and its entrance is slowly revealed when you reach a parking lot that arcs a quarter turn into the building and hugs a manicured memorial lawn. The museum presents as a monolith of cubic volumes defined by stainless steel panels polished to a matte finish, which faintly reflect what’s around it. Kristopher Takács, AIA, a DC-based director at SOM and project architect for the museum, says this is meant to give the Army and its museum’s patrons something “universal and contemporary.” While the reflection is faint, every line and every corner of the building is laser sharp, meant to evoke the precision of the soldier, according to Takács. In its volumetrics, it is meant to evoke the clarity of the Army’s mission. “The design we implemented ended up being our realization of what we think is the essence of the Army and how it exudes excellence,” he says.

Nothing about the building necessarily says “museum,” and this actually suits the different moods of its visitors who have come for a variety of reasons. On the day I visited, I watched parents corralling their children in front of touch-screen monitors. I passed veterans solemnly contemplating a cavalry saber or a surgeon’s saw in the display cases. I encountered couples quietly chatting about their active-duty sons and daughters and when they might see them again.

The first evidence of museum programming appears in the museums forecourt, designed by AECOM: A series of steles etched with the portraits and personal histories of seven soldiers. It’s a modest gesture, but one that carries through to the rest of the museum in various guises to say this is more than a repository of artifacts. This is a big story about national defense defined by the much smaller stories of individual sacrifice and mettle.

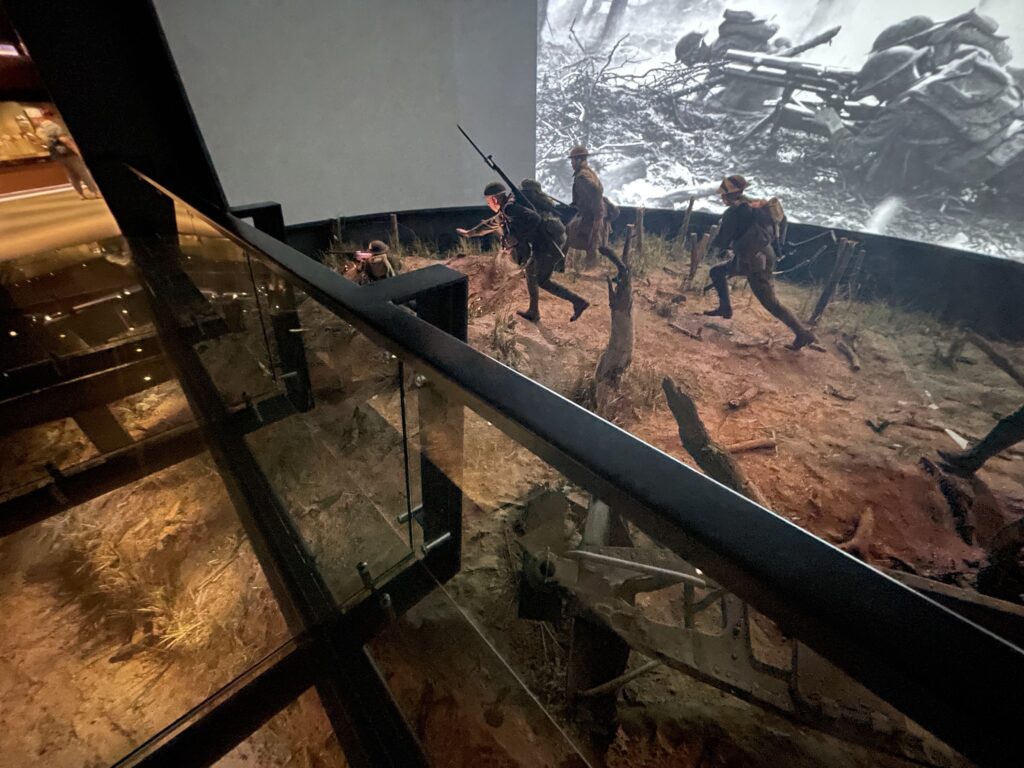

Artifacts and ephemera alike are bountiful and beautifully presented to support broader narratives about the origin, growth, and impact of the Regular Army, the Army Reserve, and the Army National Guard. As narratives go, curators have addressed the through-lines that define every era of service through voluminous wall text and interactive panels. But, they have also taken a warts-and-all approach in revealing the tensions that also define every era of service told through the artifacts: The regimental dead’s flag, the pack mule’s blinders, the enemy’s barbed trench club, Patton’s Renault tank, MacArthur’s summer service cap, Baghdad’s rubble, plate armor’s fatal piercing.

“The initial goal is to make a connection with the visitor, from an exhibit perspective, storyline perspective, and from the artifacts themselves. I want visitors to come away learning something about the Army’s history,” says Paul Morando, Chief of Exhibits there. “How are visitors connecting with our tableaus? To the artifacts? My personal goal is, when we develop new exhibits, to create new stories based on the Army’s extensive history.”

The permanent, object-oriented chronology runs from 1775 to today, and it’s a satisfying and coherent teleology that unfolds, room by room, in the eastern half of the building. In the western half, interactive exhibits cater to school groups and digitally adroit teens engaged in STEM curricula. The rooftop garden, designed by LPDA, based in Sterling, commemorates the Medal of Honor in a contemplative space away from the thrum of museum-goers. Nearby, a temporary exhibition gallery — where Morando and his team can pursue “new” stories, and currently showcasing military art and artists — offers a more conventional experience of white walls and movable partitions.

“The architecture doesn’t shape how you read things, but accommodates the multiplicity of experiences in a rigorous way,” says Takács. “It’s a museum about the American people and the American spirit, and the museum itself is meant to be stoic and strong and dignified, like a soldier.

In its programming and circulation aimed at unifying disparate audiences, the museum achieves what SOM’s Takács calls “social infrastructure.” As you pass between exhibits on one level, or move up through the building, changes in the function of spaces are subtly marked by thresholds connected to a series of wooden ribs along the wall, offering glimpses of the outside. Takács calls them “gaskets.” The “mixing chamber” metaphor uttered by architects of a certain training and vintage (and not, in full disclosure, uttered by Takács) may be applied to the building’s lobby. Yet, as sleek and contemporary as that lobby appears, it is traditional in its vocabulary of symmetries, visual hierarchies, and clear choices for museumgoers.

While these subtle hints play in the background for visitors, they are confronted at every turn with a rich material palette of granite, marble, glass, and steel that commands the kind of reverence befitting a museum designed for this purpose. But, these aren’t just appropriate museum materials. They represent a museum that’s here to stay as a place of memory and education, and they stand in contrast to the fleeting stuff of life in the vitrines beyond.

Leather. Rubber. Kevlar. Canvas. Creosote. Wool. Wood. Bone. Shrapnel. These are the materials, in the end, of an army.

About the Project Team

SOM: National Museum of the United States Army, Ft. Belvoir

Landscape Architect: AECOM

Completed 2020

Project Team: Brandston Partnership Inc.; Christopher Chadbourne & Associates; Clark Construction Group; Crystal McKenzie, Inc.; Design and Production Incorporated; Draper Aden Associates; Eisterhold Associates; Hopkins Foodservice Specialists, Inc.; M.C. Dean; Shen Milsom & Wilke; Southland Industries; The Scenic Route; Thornton Tomasetti; VDA

About the author

William Richards is a writer and editorial consultant based in Washington, D.C. From 2007 to 2011, he was the Editor-in-Chief of Inform Magazine.