Bills for both the Virginia House and Senate to study the capabilities of “point access block” construction and push for an amendment in the Virginia Construction Code are making their way through the legislative review process this month. HB 368 and SB 195 were sent to the House Committee on Rules on Jan. 6 and the Senate Committee on General Laws and Technology on Jan. 8.

SB 195 passed with a unanimous vote (with one abstention) at press time.

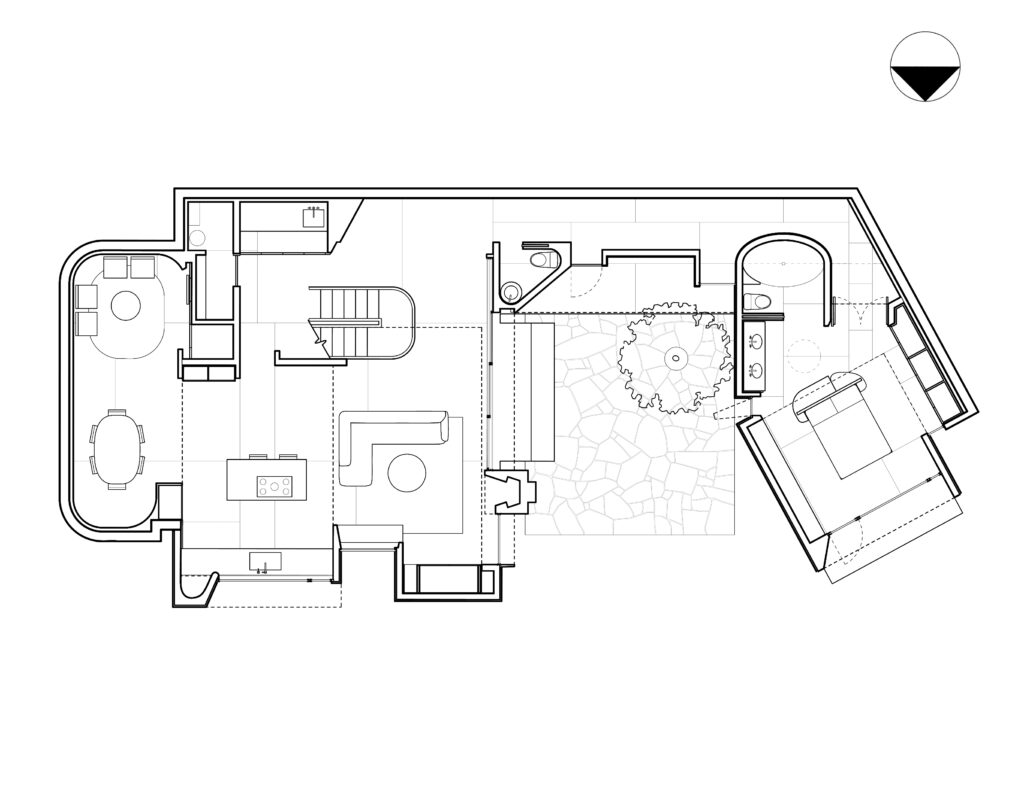

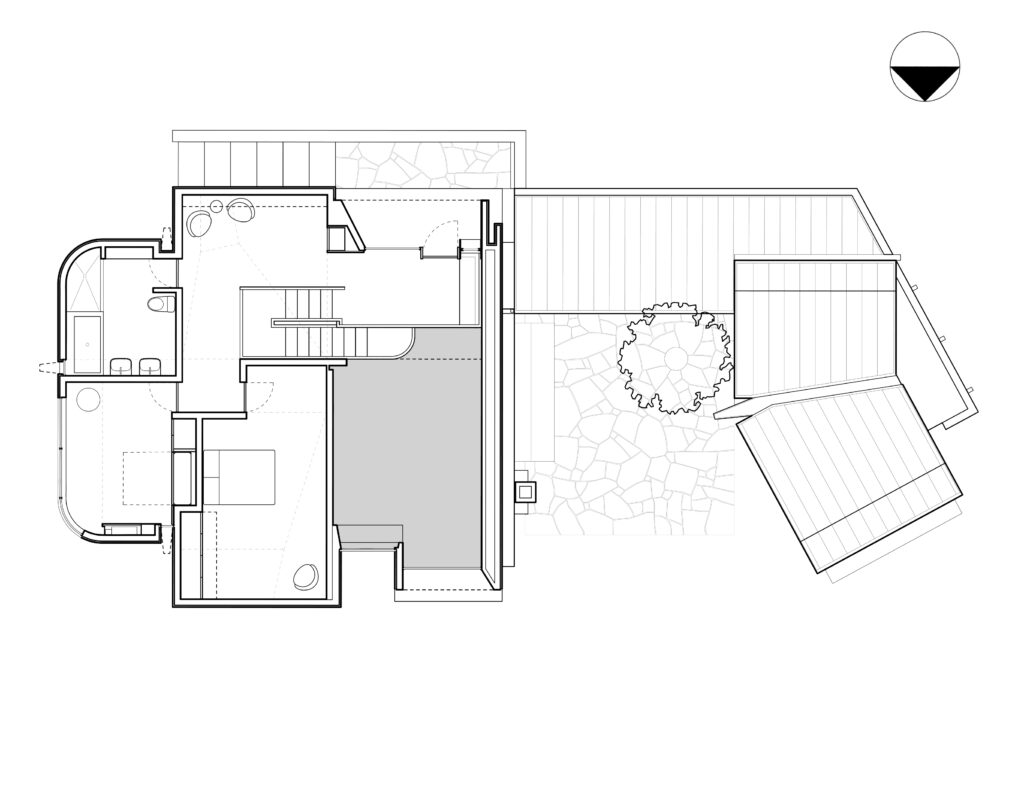

The code amendment was raised by Charlottesville-area architects and planners in 2021, which encourages the development of multi-unit buildings higher than three stories to be connected by a single staircase and access point—a building type often seen in older apartment buildings, but now outlawed in new construction today. The current requirement for multifamily buildings taller than three stories is to have two staircases lead to a series of double-loaded corridors, which often result in large floor plates and large units on either side of the corridor that, when priced competitively, exclude many Virginians living on modest budgets.

Advocates of HB 368 / SB 195 believe that, if passed, would offer the chance to consider greater flexibility for designers and owners to create a range of housing types and, as a result, counteract some of the effects of gentrification and improve the economic, social, and racial diversity of neighborhoods and communities.

Inform sat down with William Abrahamson, AIA, a senior associate at Grimm + Parker, and Gillian Pressman, a managing director of the nonprofit YIMBY Action, to find out about why this legislative action matters and what architects and planners around the Commonwealth can do to support it.

Q: Where’s the common ground between architects and YIMBY Action?

GP: YIMBY Action is a network of local groups of community members who want to see more housing in their communities, and that’s largely because they’ve been harmed by the affordability crisis, the environmental crisis, and the housing scarcity crisis. We include architects and developers who have personal and professional interests in this, but we’re mostly neighbors who want to see more affordable housing in our communities. We value our architects and all of the folks in the building industry. We show up on building sites. We address systems change like legislation. We have four chapters in Virginia, and we formed the Commonwealth Housing Coalition, which includes the National Association of Homebuilders, AARP, various faith-based groups, people along the entire political spectrum, people working to end poverty.

Q: If I’m one of the thousands of architects who works (or has worked) on multifamily projects in Virginia, what will this allow me to do for future clients and their residents?

WA: This really expands the toolbox architects can use to unlock the value of infill sites to increase density. It also helps to increase unit and demographic diversity. Removing long, dark double-loaded corridors will expand opportunities for family-oriented units with more bedrooms in stacked flats. Point access blocks facilitate more double-aspect units with greater daylight and opportunities for cross-ventilation. These will also help us create more mixing zones and unprogrammed “third-places” where residents can meet, enjoy light and greenspaces, and develop new practices of community. Current codes, construction costs, and zoning ordinances drive most urban affordable housing developments toward overly large, four or five-over-one boxes. Aside from luxury townhomes, high-rises, or retrofits, there are very few alternatives. Most families looking for somewhere to live close to jobs and entertainment are seeing the same thing over and over, and it often is not a good fit.

GP: I think the ability to influence the state legislation process as one person is way higher than you would expect. Not many people actually contact their legislators. Getting a bill that has community members who have called in about it, makes it really stand out. You can have a powerful impact.

WA: On the radio this morning, state representatives were describing dropping school enrollments and that families are leaving Virginia. It is inefficient and expensive to build three-bedroom apartment flats. It’s expensive to build townhomes. In these double-loaded corridors, you have narrower apartments, fewer bedrooms, less daylight, worse ventilation—because of high construction and financing costs. That’s where the square footage efficiency of point access blocks stands out—it’s much higher.

Q: We know how gentrification can boost the tax bases of cities, but we also know that it comes at a much higher cost than land acquisition and construction. Is this enough to counteract outpricing and the erosion of neighborhoods and communities? Or is this code change better paired with other strategies?

WA: Unit mix is a dry term, but right now in a typical development, it might be 80-, 90- percent of a single unit type. With taller point-access blocks, you can have one-, two-, three-, or even more bedrooms in efficient configurations. This allows a growing family, a retiree, a middle-aged couple, or a single person to all find appropriate homes in a building AND to stay in their communities when they need a change in housing. It is a way of addressing the stratification of society, by blending all these types of life stages under one roof.

GP: When people talk about gentrification, most of the time they are talking about displacement; which is people of color living in urban cores losing their homes as richer people come in and outbid them.. YIMBY Action is vehemently against displacement. Our solution to displacement is to build more housing! YIMBY Action believes that the entire region needs to build, not just specific sections of the urban core. We have made it so that the only place to add development is in urban cores, so a lot of the area in the city are low density or suburban areas—we have made it impossible and illegal to build generous amounts of housing there. So, then what happens, only the sections of the urban core with disenfranchised populations can be developed—which is driving gentrification. Where there IS building in urban cores, it cannot and should not be displacement housing. It’s fine to get rid of old buildings that pose a health risk. But, we cannot displace people when that happens. Our ideal is that exclusionary suburbs that make up a region also share the housing burden that cities are asked to bear.

WA: It’s a question of scale, too. The bill allows up to six stories, which sounds high compared to most single-family zoned units, but the alternative is a mega-block. This bill allows the kind of density that’s productive and flexible.

Q: Advocates of this strategy cite European cities as offering a healthy and diverse mix of residents because they are zoned differently. What sort of ripple effect would this create beyond Virginia in the United States if it’s successful?

WA: Virginia is held up as one of the top building code adaptation processes in the country—we have some of the most rigorous standards of public engagement, feedback, and engagement with code officials. So, if a measure passes here, it carries a lot of weight. There’s a second stepping-stone to this issue, which is elevator codes. Point access blocks would benefit from the smaller, cheaper elevators found everywhere except the U.S. The U.S. requires unique testing requirements and safety testing requirements, so any vendor selling here must pay gobs of money to participate in the market. However, if you look at safety testing, there’s no loss — it’s not as if other countries have any higher rates of elevator failures. But what it means is our elevators are much more expensive to implement, maintain, and operate. This presents a hurdle to market adoption.

GP: The biggest thing is that this is scalable. This isn’t a code problem or a design problem. It’s a political problem. We think communities can be and should be more diverse and walkable and vibrant, but people are scared of that. There’s a culture in planning schools and local governments about deferring to what they think local constituents want. But, the constituents that planners and local governments have historically heard from are NOT representative. The people that show up to public meetings are neighbors who don’t want something to happen because of noise, nuisance, or a change that will affect their private property. People who are angry are motivated to come out to these meetings, and the voices of “no” drown out any positive philosophies of “yes” that could be present. We have to be representative in our politics and organize people to come out and be the voices of “yes.” We also have to encourage planners and local government leaders to engage in more representative community-wide planning processes that take the true views of local neighbors into account; instead of being swayed by an unrepresentative group of the angriest neighbors.

WA: Adding to that, if someone doesn’t feel they have agency, they tune-out changes, good or bad, in the built environment. Public officials may have low literacy when it comes to community development principles. So who is going to take the time and energy to look at this issue? Opening up this aspect of building form allows the professionals and the market to present new ways of building and living.

Interested in learning more and participating? Check out the Commonwealth Housing Coalition to find out how you can help.