Virginia’s first railroad, connecting Petersburg south of Richmond with Garysburg, North Carolina, on the eastern side of the Commonwealth dates to 1830. That general direction and course would define most of Virginia’s commercial and passenger railroad activity, even as it sprawled into the sizable network of lines today. But the western lines are arguably more beloved for their scenic beauty, and the ones running in the shadow of the Blue Ridge Mountains have been a vital link for communities like Abington, Bristol, and Radford, well beyond the historic end of the line in Lynchburg. Some of them have been transformed, like the Abington Branch of the Norfolk and Western, disused since 1977, which has become the Virginia Creep rail-trail. Others remain active, such as the old line first started by the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad Companies in the 1850s, which still runs through Radford, where Virginia Tech architecture students completed the New River Train Observation Tower in November 2019.

Led by architects and Virginia Tech faculty Kay Edge and Edward Becker, Intl. Assoc. AIA, the tower sits on the property of the Radford Heritage Foundation’s Glencoe Museum and overlooks a 1.3 acre riverside site donated by Norfolk Southern Railways. It’s part of a multiyear initiative by the city’s Tourism Commission and Radford Heritage Foundation to develop the Mary Draper Ingles Cultural Heritage Park. The goal, shared by so many American cities who have transformed their underutilized waterfronts in the past two decades, has been to tell the story of an industrial and cultural heritage. But, in service to that goal, Radford has also become a site of architectural experimentation.

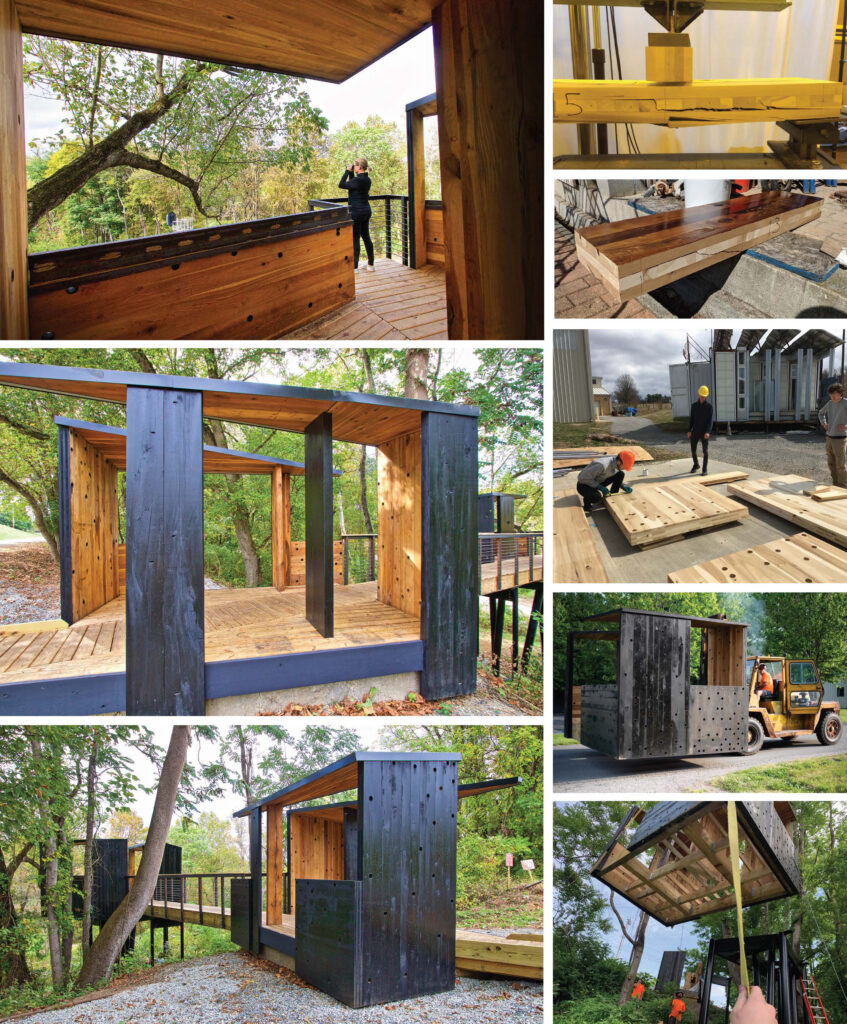

Edge invited Becker to join the project after she led students through the site analysis, research, design, and construction over several semesters. Arranged in two volumes connected to an access path and by a footbridge, the project mirrors the conjoinment of two rail spurs a few dozen yards away. Edge and Becker utilized cross-laminated timbers (CLT) derived from hardwood yellow poplars in contrast to the soft words usually used for CLTs, but also as a strategy to limit the project’s carbon footprint.

“If we had gone a traditional route, the material would have had to come as far away as the Pacific Northwest,” says Edge, “but I happened to attend a class one of my colleagues gave in sustainable biomaterials and learned about hardwood CLT, as well as the potential of local wood to be used. So, I contacted some mills and they donated the material.”

For Becker, the macro-level story is not just about carbon, but the promise of code revisions to boost sustainable building practices and local economics.

“Our colleagues in sustainable biomaterials are very much focused on gaining the code approval of a project like this, since southwest Virginia, West Virginia, and other rural places that have resources like hardwood yellow poplars could benefit substantially if there was code approval.”

In 2020, AIA Virginia recognized the project with an Award of Merit in its annual Design Awards. Jurors cited it as a superb example of collaboration and experimentation in service to a broader effort to celebrate local history in the 21st century. For Edge, it might well be a catalyst for future studios centered on the New River site.

“Students spend so much time in front of their screens that I worry about them developing a sensitivity to building materials and construction,” she says, “I’m always looking around for students to build stuff and I’d like to find another opportunity like this.”

About the Author

William Richards is a writer and editorial consultant based in Washington, D.C. From 2007 to 2011, he was the Editor-in-Chief of Inform Magazine.