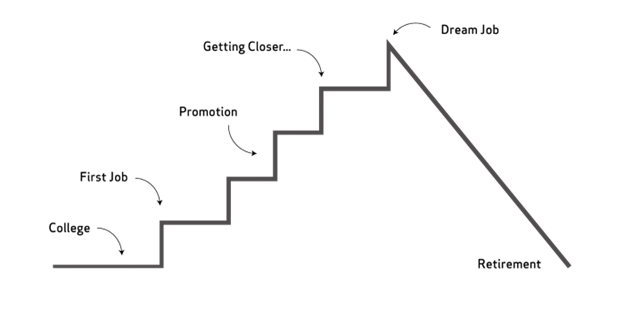

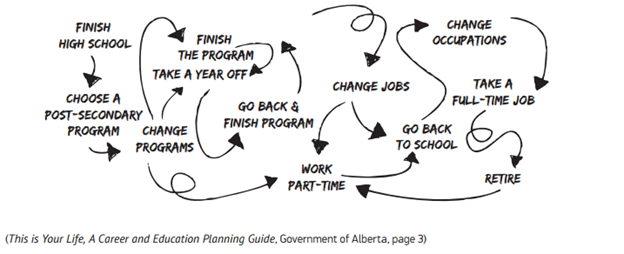

According to Fisch and McLeod’s popular video, “Did You Know,”1 “we are currently preparing students for jobs that don’t yet exist, using technologies that haven’t been invented in order to solve problems that we don’t even know are problems yet.”1 During previous generations, the path from high school to adulthood was linear: eighteen-year-olds went off to four years of college, graduated, and then entered the workforce. White-collar professionals climbed the corporate ladder by learning managerial-based skills on the job and had, on average, only six job changes from college to retirement. But today’s career trajectory is more agile and unpredictable.

Given the short lifespan of technology, skillsets can become obsolete before a student graduates. Our most promising professions are related to knowledge creation and innovation — soft but smart skills, breadth, depth, and interdisciplinary teams. The US Department of Labor estimates that today’s learners will have ten to fourteen jobs by age 38. But as the workforce emerges from the pandemic, we have fundamentally shifted who is in control in the workplace and where the production takes place. Workers are no longer solely focusing on what we earn — we also care about what we learn, where we learn, and how work balances with life.2 The live-work-learn cycle is a continuum as learning has become a lifelong, life-wide, life-deep activity. Our learning environments are no longer about information dissemination but knowledge construction through information deconstruction. Learning is active, hands-on, and experiential. This paradigm shift has had and will continue to profoundly impact the layout and design of our physical post-secondary learning environments.

If how we learn, where we learn, and with whom we learn is rapidly changing, and the toolbox of space types and furnishings that make up a college campus are no longer predictable, where can we turn to understand the learning environment of the future? How can we digest and dissect possible scenarios to ensure our designs are pragmatic enough to elicit approval and funding yet nimble enough to adapt to new technologies and ways of learning?

As a Learning Environments Strategist at Ayers Saint Gross, I talk with institutions around the country about emerging higher education trends developing on their campuses and how physical space will evolve to meet their students’ current and future needs. For these conversations, I repeatedly turn to a few valuable resources to keep abreast of trends:

- The Center for the Future of Libraries3

- Educause’s Teaching and Learning Edition of the Horizon Report4, and

- Bryan Alexander’s Future Trends in Technology and Education5 newsletter.

Like many other trend-watching sites, the resources loosely organize trends via a STEEP analysis. STEEP is an acronym for Sociological, Technological, Economical, Environmental, and Political. A STEEP analysis maps external factors that influence an organization or category — in this case, higher education. Studying trends helps bring perspective to the higher-ed market and shape possible future adaptations needed. Armed with knowledge of possible futures for education, we can design forward-looking, agile spaces ready to respond to a breadth of pedagogies, technologies, and experiential needs. Trends consistent between the three sources include connected and experiential learning, hands-on making and meaning, artificial intelligence, and augmented and virtual reality. Potential threats to higher education include the devaluation of the college diploma, political instability, the impact of Covid19 on K–12 learning, and the mental health and wellness of stakeholder populations. These trends point towards a future that is less compartmentalized — a future more focused on experiential learning and hands-on, minds-on creation. But they also point towards the need to find alternative methods of delivering learning-at-scale, especially at larger public institutions.

An institution here in Virginia that is exploring active learning-at-scale is Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU). VCU’s McGlothlin Medical Education Center, designed by Pei, Cobb, Freed and Ballinger, houses four learning studios stacked vertically on floors 5-8 of the building. Each classroom holds 132 students at eleven 6-person Steelcase Mediascape tables. The tables have two monitors — one for the instructor to stream video and the other for the students to use as a working monitor. Tables also have outlets and ethernet connections. Additionally, each 132-student room can be divided into two 66-student rooms via a ceiling-mounted room divider. Each larger room has six projectors and screens, and the walls are painted with whiteboard paint for a continuous whiteboard surface. Instructors can teach in a single location and have the lecture simulcasted to the other rooms. After the lecture portion of the class is done, the instructor can travel from floor to floor and classroom to classroom to help students that may need additional in-person assistance. By offering a scalable solution, these four floors can flex to accommodate class sizes from approximately 40 to 528 students in-person. Jay Brazelle, the Senior Supervisor at VCU’s McGlothlin Medical Education Center, shared with me that not a single professor has requested an auditorium for their sections since VCU has returned to in-person courses post-pandemic. The auditorium is now used only for special events such as awards ceremonies and testing. Additionally, VCU has compressed four semesters into three by removing redundancy across courses through this inter-professional, collaborative model.

Reviewing trends from the resources above, it’s easy to begin imagining a future where universities evolve into an ecosystem of physical, virtual, and social spaces that revolutionize opportunities for learning and connection but do so with scale and reach in mind. Built environments could shift away from passive classroom and office environments towards interdisciplinary living lab research centers, expanded project-based space for making and prototyping, industry-adjacent start-up centers, and wrap-around services focused on holistic wellbeing. Learning spaces will likely merge in-person and telepresence options, loosening restrictions around attendance, credit hours, and sequencing. Space solutions will instead capitalize on haptic technologies to augment experiential learning and bring the learner closer to the source of knowledge.

What additional types of physical space may be required so that students continue to consider the physical campus a vital value-add to a degree program? What additional simulations and AR/VR reality experiences may be around the corner? And how can we ensure there is flexibility in our designs for this type of creative experimentation around evolving learning strategies? A trends assessment can help to understand what is emerging in the world of education, how we may see universities advance future innovations, and what design and planning efforts may look like in the coming years.

References:

1. Fisch, Karl and McLeod, Scott, “Did You Know (Officially updated for 2022)”. uploaded by Did you know, January 22, 2022. www.youtube.com/watch?v=kCTAoQsSXpo

2. McGowan, Heather. “Adaptation Advantage: Leading in a Post-Pandemic World”. Society of College and University Planning SCUP 2022 Annual Conference, July 24, 2022. Long Beach Convention Center, California.

3. “Trends”, American Library Association, August 8, 2014. http://www.ala.org/tools/future/trends (Accessed August 22, 2022)

Document ID: 8fbf22e4-7906-19a4-3952-5e79077a9596

4. Pelletier, Kathe et al. (2022). 2022 Educause Horizon Report Teaching and Learning Edition. Boulder, CO: EDUCAUSE. Retrieved August 22, 2022 from https://library.educause.edu/-/media/files/library/2022/4/2022hrteachinglearning.pdf?la=en&hash=6F6B51DFF485A06DF6BDA8F88A0894EF9938D50B

5. “Future Trends in Technology and Education.” Bryan Alexander, 24 Sept. 2018, https://bryanalexander.org/future-trends-in-technology-and-education/

About the Author

Shannon Dowling, AIA, LEED AP, is a Learning Environments Strategist at Ayers Saint Gross and a 2020-21 SCUP Fellow. She is working with Virginia Union, Virginia Commonwealth University, and the University of Richmond to research ways diversity, inclusion, and equity can take a physical shape on campus.