The word innovation isn’t just a rejoinder to the debate in education about value these days. It seems to also suggest a new typology of flexible and adaptive spaces. Virginia Tech is currently developing a four-acre Northern Virginia Innovation Campus in Alexandria, which will open in 2024 with a 300,000 square-foot Innovation Center Academic Building (ICAB) designed by SmithGroup. Its principal-in-charge, David Johnson, AIA, says that the emerging typology is less about form and more about accommodating the changing needs of an array of user groups. “The intellectual framework for the innovation center is about accelerating ideation and discovery by bringing together competing and interdisciplinary interests,” says Johnson, “but to be more precise, most, if not all, of our design goals were related to human centered design.”

To test some of these goals and also provide an administrative hub for Virginia Tech executives charged with creating a campus out of whole cloth, SmithGroup’s Sven Shockey, AIA, has designed a 5,000 square-foot start-up space in the existing National Industries for the Blind building just south of the larger innovation campus.

“The start-up space was conceived because Virginia Tech wanted an immediate presence in the neighborhood,” says Shockey,” and so it needs to accommodate every possible objective from administration to fundraising to industry relations.”

It’s shaping up to be Virginia Tech’s best foot forward: airy, light-filled, graphically bold, and “lightly” programmed in an approach that’s become more and more common at the vanguard of working and learning spaces. But, this approach is not meant to transform workers (or future students) into virtual interns for Silicon Valley. It’s meant to tap into something fundamental about shifting expectations about how we interact with our work and each other.

“Innovation centers allow a host of possible outcomes to happen, which is exactly what we wanted for this space. They provide a place for potential to be realized, but not in an over-programmed way. They want to be raw, but have amenities,” says Shockey. “You have to ask yourself what are the universal things you can provide in a project to allow anything to happen? It’s simple: daylight, air, adjacency, and flexibility, not to mention inspiration.”

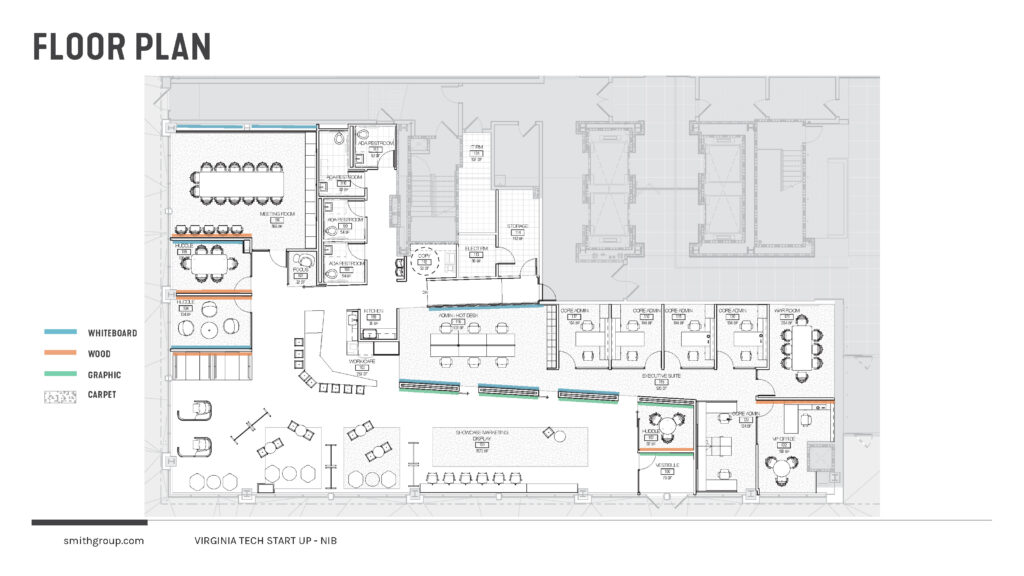

In plan, the start-up space represents an “L” on the floor plate, cosseting one corner and offering passers-by a glimpse in from the south and west, as well as all-important views out at street level. But, within the “L” are two more “Ls” nested within one another to create distinct workspaces, from single offices to group pods to conference spaces that accommodate both prescribed workstyles and freeform engagement. As team needs telescope from ideation to break-out testing and conversation, the space can respond. As an individual’s workload shifts throughout a week, the space can accommodate it along the full spectrum of private to public.

This idea of nesting extends to the start-up space’s section, too, where the industrial chic of exposed utilities above peek out from behind felt ceiling panels that, in their fractal appearance, are a nod to the ICAB that will break ground shortly. SmithGroup used what they call a “packing algorithm” to create them out of single sheets of material for easy packing, unpacking, and installation, saving resources and cutting down on the carbon footprint of the project.

If innovation corresponds to a direct visual form, it might very well be the ICAB itself across Potomac Avenue. Its geometry has variously been described as angled and sculpted and its design responsive to the sun’s arc, maximizing the amount of photovoltaic energy that can be captured with conventional panels and photovoltaic glass, which will effectively multiply the building’s performance.

At the elementary and high school level, “innovation” usually attaches to a STEM curricula and a laboratory approach to test conventional ideas about learning spaces—the Lamplighter School Innovation Lab (Marlon Blackwell Architects), Peach Elementary School (Perkins+Will with Glenn Partners), and the PAST Foundation (WSA Studio) come to mind.

But, the average 7th grader studying data structures and a veteran office employee on an agile scrum sprint have more in common than you might think when you consider how faint the line is between learning and working. They demand the same basic conditions for success, and innovation centers begin with those conditions in mind: openness, flexibility, and control over one’s environment.

Johnson and his team used various personas to map out the building’s future for Virginia Tech, including that of a middle-schooler who, when she gets older, learns more about technology and comes to this innovation campus to study it.

“There was a sense that computer engineering needs to be in service to humanity, so we wanted to embody that in the building. That’s where we began,” says Johnson, “and I think we have a strong chance of realizing that vision.”

About the author

William Richards is a writer and editorial consultant based in Washington, D.C. From 2007 to 2011, he was the Editor-in-Chief of Inform Magazine.