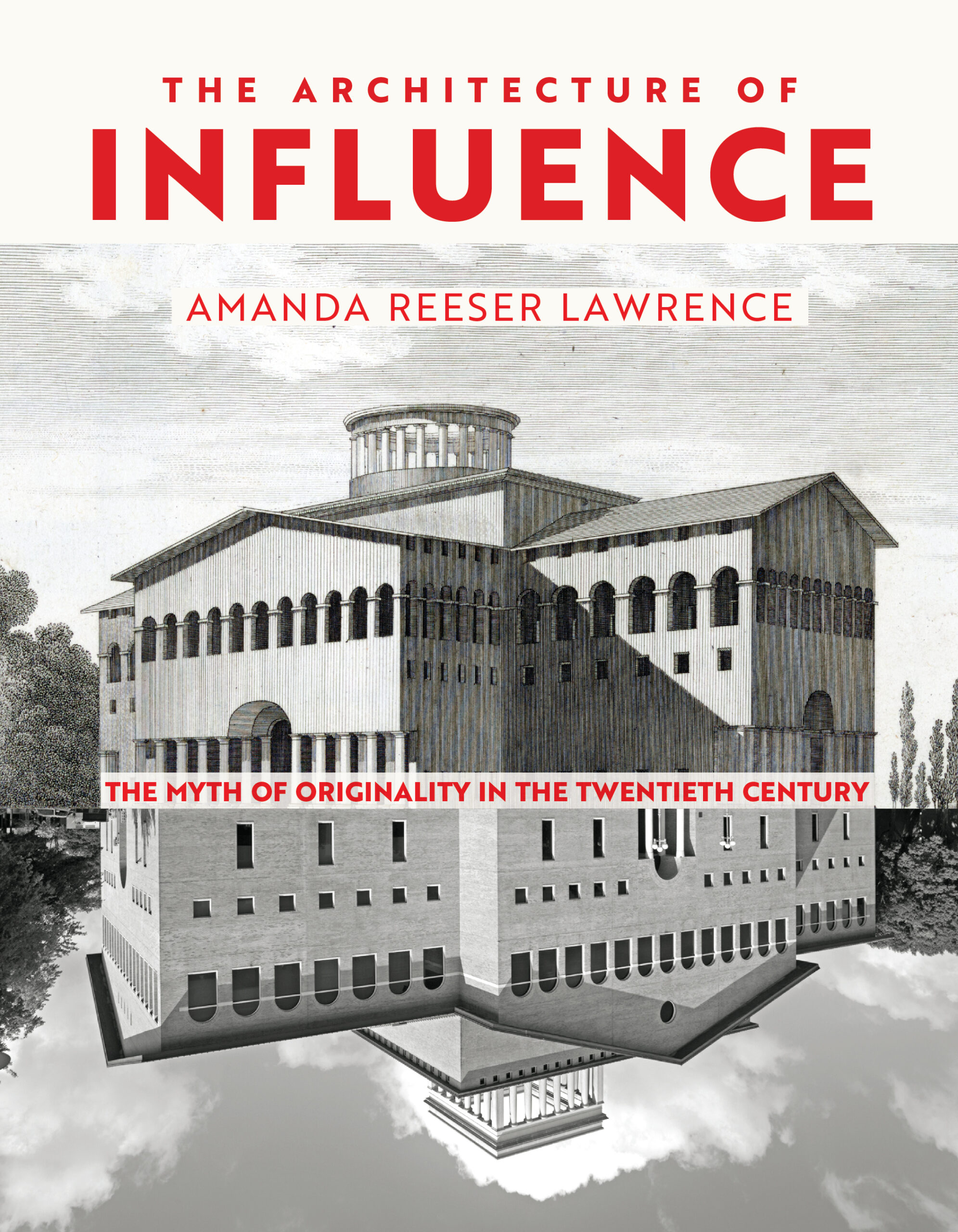

Amanda Reeser Lawrence’s new book, The Architecture of Influence, casts aside the easy explanation of architecture as a stylistic evolution—the Romanesque begat the Gothic begat the Renaissance, and so on. By looking at replicas, copies, revivals, and other categories we use to describe architecture, Lawrence, an architectural historian and Associate Professor of Architecture at Northeastern University, helps us connect the dots on architectural production in two different ways—first by focusing on production, itself—the evidence of building rather than the intention of invention—and, second, by looking at the vocabulary we use to talk about that evidence. If you think this is a purely academic argument, you’d be wrong. This book is about the creative process and how influence is courted, leveraged, and considered in the work of architects of every stripe—from the academy to practice. “After 15 years of teaching and being part of reviews, if students deliberately elide this question of influence,” she says, “it creates a strange disjunction where others see the influence of their work even if they don’t.”

The subtitle of this book about the “myth of originality” in architecture is maybe more telling than the title. What is this myth and why are we, as a culture, so content to believe it?

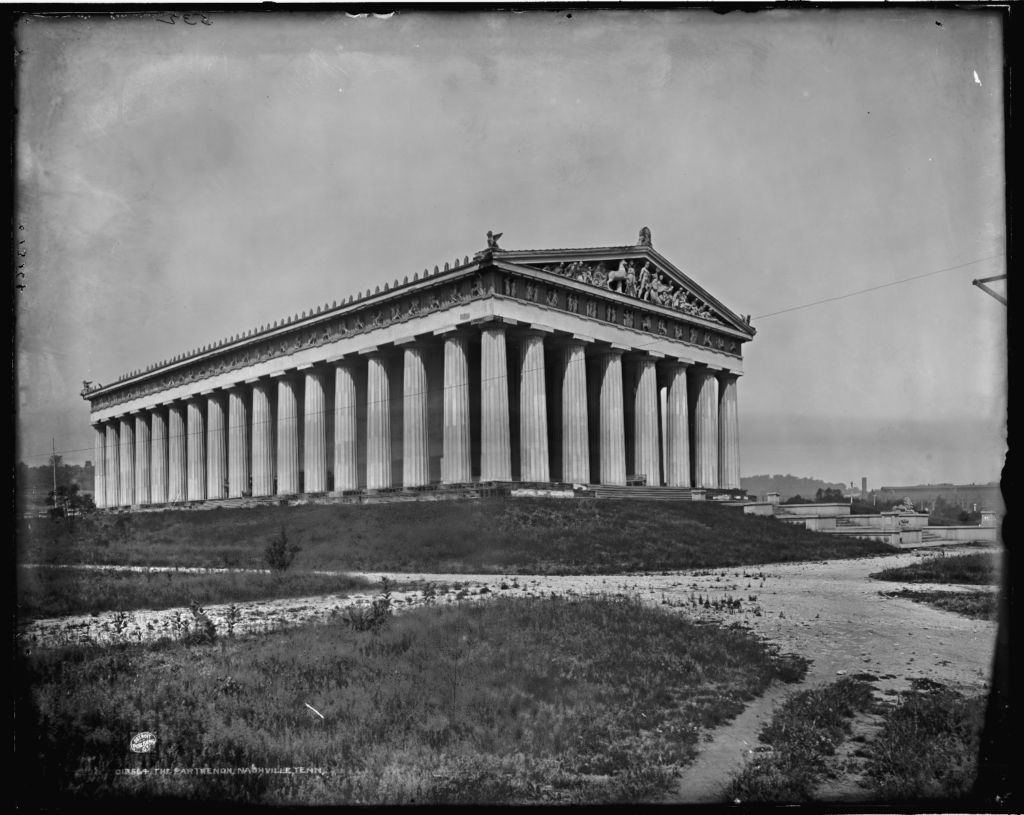

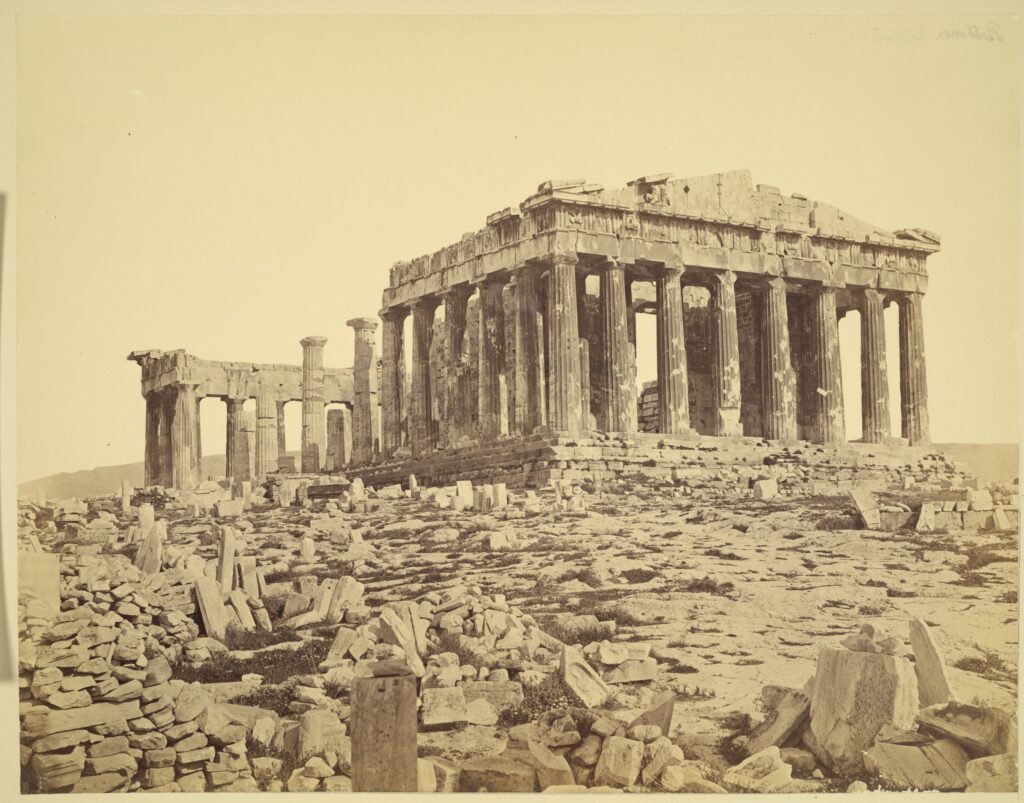

This is a good question—why do we hold on to the myth of originality? I think it connects to the concept of “genius” and the desire for the new. I’m trying to debunk the idea that every architectural work has to be understood only as “new,” and claim instead that every work is also indebted to what’s “old.” Every work is both singular, which is to say unique, and connected to what’s come before. That comes across most clearly in the chapter on “replicas” because replicas are, seemingly, the least original type of architecture. The Parthenon in Nashville, Tennessee, for example, is a replica of the well-known structure in Athens, but it is no less a unique work of architecture than the original on the Acropolis. The architects of the Nashville Parthenon had to make decisions about structure and siting and materials and construction. So, the “myth” of originality is that only seemingly novel works are original.

Images courtesy University of Virginia Press.

There’s an arc of influence that was particularly potent for a recent generation of architects: Ruskin and Viollet-le-Duc are both reconsidered heavily in the 1970s and 1980s, and a decade later, there is an obsession with the architectural palimpsest. Why do we find the work that Ruskin and Viollet-le-Duc represents, and the palimpsest so compelling—still to this day?

Because it gives meaning to the work. It’s about making connections. There’s a lot of discussion around plagiarism right now in the world, and that is an interesting development as we contemplate this idea of drawing from the past. All architecture is plagiarism to some degree. But what I find more interesting is to consider how architecture borrows from the past. The past informs the present, of course, but we also understand and redefine the past through the present. In the work of Kahn or Venturi, for example, we find embedded references to fundamental architectural ideas like “pyramid” or “house,” but we then see pyramids and houses differently through their work. We realize that architectural ideas aren’t fixed things, but open to reinterpretation.

I was very careful in the book not to focus on architects’ intentions. The critic and the historian have a place to offer their interpretation, regardless of claims made by the architects in question.

I think the critique of genius is important, too. For that reason, I focus the book on works of architecture rather than the architects themselves—on the building as the site of inquiry. But this doesn’t mean that we do away with the figure of the architect altogether. In the chapter on “emulations” I address this specifically—for example, when Schindler is working in Wright’s office while Wright is away in Tokyo, Schindler struggles with this question of how much of himself to put into a “Wright” work.

When you talk about the Renaissance, there’s a developed conversation about copies—but we’ve forgotten how to talk about it. Why?

It’s a postmodern hangover. After that era, we stopped talking about influence, at least explicitly. My first book was about James Stirling—a postmodernist who refused the term postmodernism, but who, I argue, was explicitly “revisioning” the work of others.

Even now, I think many in the field are reluctant to talk about ideas like influence and unoriginality. In fact, this book, The Architecture of Influence, had a bumpy road to publication, as a number of readers who looked at the proposal were uncomfortable that I juxtaposed people and ideas from across different historical periods and styles, or even that I used the term “influence” at all. So, at the beginning of every chapter, I spend time defining terms—words like replica, copy, imitation, and emulation—to show the reader what they mean in architectural culture, but also how they’ve developed historically. As a professor of architectural history, I teach a lot of architecture students, and it was important for me to help them discover a vocabulary through which to talk about these ideas in architecture.

Words like contemporary versus traditional and new versus old—these are words that a lot of people use to describe the things they see in the world. How did you think about these simple, everyday terms?

I obsessed and gnashed my teeth over over those words! Binary concepts such as new/old or modern/traditional are embedded in our consciousness, and there is an assumption that traditional architecture looks to the past, while contemporary or modern architecture does not. In the book I try to break down those distinctions, and talk about how the past is referenced and reimagined in all types of architecture. In the chapter on “revivals,” for example, I intentionally look at two examples that exist at opposite ends of the stylistic spectrum. One is a dormitory that “traditionalist” Demetri Porphyrios built at Princeton in 2007, where you feel like you’re in a time warp, transported back to the 12th century (with air conditioning!) The other is the “modernist” work of Peter Eisenman, who was teaching at Princeton when Porphyrios’s building was completed, and found it incredibly problematic. But, the argument I make is that work of Eisenman and the rest of the New York Five, which references Corbusian modernism of the 1920s, is conceptually no different than Porphyrios’s reference to twelfth-century Gothic. Both were riffing on earlier ideas. Neither references a specific building—instead they bring earlier stylistic languages back to life.

What about the myth of the architect?

Throughout the book, but especially in the last chapter, I look at the work of architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Frank Gehry, Mies van der Rohe, and Zaha Hadid through the lens of repetition. There is undoubtedly a signature attached to the work of these architects, which we can understand as a type of self-influence, and also as a rebuke to the ideas of “originality” and “genius.” Mies speaks most eloquently about this—he famously said that you can’t make a new architecture every Monday morning. I understand that remark as a form of resistance to a capitalist imperative for the “new,” but it is also, of course, an embrace of unoriginality. Interestingly, Frank Gehry has a different perspective on this idea of self-repetition—he says something to the effect of “I could never face my children if they thought I didn’t have any new ideas.” And yet, there is a self-sameness to his work. For me, self-repetition is a yet another way to challenge our ideas about so-called “genius” and the myth of originality.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Architecture of Influence: The Myth of Originality in the Twentieth Century, by Amanda Reeser Lawrence, University of Virginia Press, 2024

William Richards is a writer and editorial consultant based in Washington, D.C. From 2007 to 2011, he was the Editor-in-Chief of Inform Magazine.